Now on sale as both a paperback and e-book: http://booklocker.com/books/6965.html Also available from Amazon and other online book sellers.

“Documentary 101: A Viewer’s Guide to Non-Fiction Film” is a first-of-its-kind anthology, covering the entire spectrum of non-fiction film from 1895 to the present day. There are 101 full-length reviews of documentaries chosen for their aesthetic prominence and/or historical significance, followed by briefer entries on related titles. There are 325 total reviews and an informational appendix in its 418 pages.

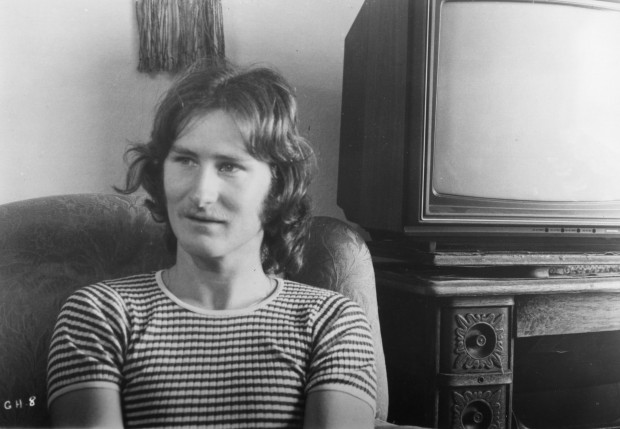

The relocated deceased pets are given a final final-resting place at the Bubbling Well Pet Memorial Park run by Calvin Harberts and his family. His younger son, Danny, ranks above older brother Phillip due to his length of service. Danny is a soft-spoken, hippie-ish young man who plays guitar and is the sole occupant of a hilltop bungalow overlooking the park. He seems indifferently fated to inherit the family pet cemetery as he sits in his room surrounded by stereo equipment and a TV, talking up vague notions of love and rock ’n’ roll superstardom. In one well-known scene, he takes his electric guitar and his powerful amplifier outside, serenading the passed-on pets and the whole empty valley with some choice hard-rock riffs. Danny seems as dispossessed as any protagonist from a Kafka novel. It’s startling to realize how far Errol Morris has expanded from his base subject. “Gates of Heaven” is a film permeated with a certain kind of human fragility, the kind that lies just behind the veneer of people’s stoical everyday lives.

(Gates of Heaven, 1978)

*********************************

Russian director Dziga Vertov, along with fellow countryman Sergei Eisenstein, did much to pioneer the development of film montage and subjective editing. His was a cerebral brand of filmmaking, encompassing as it did patriotic movies for the young Soviet Union as well as the methodology of elevating the “life-facts” of photographic observation into a wider realm using stylistic flourishes. Vertov cleverly uses the actual making of the movie as its own framing device and along the way uses frenzied jump cuts, subliminal dissolves, overlapping images and split screens with the utmost confidence. Vertov’s stature was eventually undermined by Josef Stalin’s iron-fisted rule. Vertov may have been a committed Marxist but Stalin was an even more committed dictator and the director did not fare well when film projects started to fall under the auspices of rigid planning committees. His considerable talents and boundless creative drive were not so much crushed as gradually marginalized.

(Man With a Movie Camera, 1929)

***************************************

The haunting “voice” of the theremin, the first electronic musical device, wafted above a long stretch of the twentieth century and found its apotheosis as a creepy backdrop for Cold War-era science fiction and suspense movies, as well as on the Beach Boys’ optimistic pop gem “Good Vibrations.” Even more intriguing than the instrument’s sound is the life story of its enigmatic inventor, Russian émigré Leon Theremin. At the height of his fame, Theremin vanished from his swank New York penthouse amid speculation that the KGB had kidnapped him. He reappeared several decades later, living in Moscow. Director Steven M. Martin unearthed exceptional archival footage of Theremin’s early years when he was the toast of New York, playing Carnegie Hall and hosting grand parties at his Fifty-Fourth Street compound with paramour, Clara Rockwell, also a theremin virtuoso.

(Theremin: An Electronic Odyssey, 1995)

*****************************************

Ross McElwee was born in 1947, into an old-line Southern family from Charlotte, North Carolina. He attended Brown University in Rhode Island, where he was exposed to the socially conscious films of Frederick Wiseman. Since doing his graduate work at MIT (under the tutelage of master documentarian Richard Leacock), he’s been based in the Boston area. Under different circumstances, his first full-length film may have been a fine, straightforward doc on the notorious march to the sea by Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman. But, as film history would have it, his girlfriend dumped him just as the funding for the project was secured. Beset by self-recrimination over the break-up, McElwee headed south with something more than the siege of Atlanta on his mind. McElwee gets sidetracked over large stretches of the old Confederacy, training his camera lens on seemingly every available woman on his own path to the sea. What came out of all this was a very droll landmark in the annals of the personal film-essay style, taking below the Mason-Dixon Line the kind of cerebral romantic comedy that Woody Allen used to be famous for. But McElwee is canny enough to keep his would-be womanizing from becoming self-indulgent, and his occasional insights about the Civil War and more modern forms of annihilation keeps the interest level high despite the film’s long running time.

(Sherman’s March, 1987)