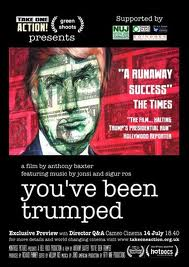

You’ve Been Trumped

Directed by Anthony Baxter–2011–95 minutes

We are obliged to live in a world with a multitude of political opinions, social attitudes and lifestyle choices. This naturally causes all sorts of random discontents when different values knock against each other. But I always thought there was one thing people all across the spectrum could agree on: that the junior sociopaths that roamed the hallways and recess yards of elementary schools everywhere—calling you humiliating nicknames with no provocation, ridiculing you for being in the bathroom too long, pushing you down in gym class when the teacher had his back turned—would recede from your life by high school at the latest and be recalled with the utmost disdain in adult life if even thought of at all. Boy, am I naïve. Just give this same asshole a trust fund and a tawdry reality TV show and, in an age of celebrity overlords and toxic conservative talk shows, you get people voting for (and even worshipping) the same pathologically insecure bully that would have once pummeled them for the milk money. And for President of the United States!! I don’t believe there’s nearly enough bamboozled voters to elect Donald Trump. But I was also wrong in thinking that nobody would ever pull a lever for a candidate that calls them “stupid” to their face, just like he would have if he knew them in 5th grade.

So the title You’ve Been Trumped neatly sums up this blood-boiling 2011 documentary directed by Anthony Baxter and produced and co-written by Richard Phinney. It’s a gritty, ground-level film witness to Trump’s vulgar tactics on a smaller scale (but blessedly without the misdirected popular support we now see in the States) as we experience Trump pushing through plans to build an enormous jet-set golf resort near a pristine stretch of coastline north of Aberdeen, Scotland. The filmmaker’s sympathies are clear as a group of local residents, who have the audacity to own humble properties in the path of the tycoon’s grandiose scheme, refuse to budge—even in the face of a government Compulsory Purchase Order (eminent domain). The starry-eyed deferment to fame and fortune in its modern media-age manifestation provides the film’s rich subtext.

The Aberdeenshire regional council at first rejects the plan but after the Scottish Parliament “calls in” that decision, the project is approved, despite the site’s official designation as a grade-one conservation area. Baxter shoots a scene at a Trump-attended groundbreaking event, where fawning local officials and business people realize that their lives are being touched by an actual Celebrity, and one ready to throw a lot of money around. A nearby college, not to be outdone, desperately bestows Trump with an honorary degree even as credible experts warn of the steep environmental cost.

Throughout You’ve Been Trumped Baxter inserts scenes from Bill Forsyth’s amiable (and analogous) 1983 fiction film Local Hero. There, the plans of an American oil baron (Burt Lancaster) to buy out a coastal enclave on Scotland’s west coast and replace it with a refinery are complicated when the hotshot executive he sends there as an advance party (Peter Riegert) is lured by the charms of the village’s slow-lane lifestyle. How quaint. Nowadays, a guy like “The Donald” doesn’t have to waste his time courting skeptical residents. According to him, the property of Michael Forbes, the flinty old-school farmer who’s at the forefront of local resistance, is “slum-like and disgusting” and the man “lives like a pig.” Trump has always liked to come on like a streetwise New Yorker (despite his silver spoon) and his blustering reputation precedes him by a country mile. This kick-out-the-poor attitude is less objectionable nowadays where (notably in the U.S.) a certain obsessive fixation on wealth and fame has elevated the likes of him to an iconic status that often “trumps” any solidarity one may have once felt with the general population.

With the skids greased by the city fathers, who seem to have imported this mindset, Trump quickly moves in. His earthmovers are soon moving “biblical” amounts of sand to make way for the two 18-hole golf courses, depositing one of Britain’s largest sand dune systems next to the homes of those who don’t like him and encroaching on their property lines. In one of the film’s more telling scenes, the local police arrest Baxter (and rather roughly at that) for filming an interview with project opponent Susan Munro, in her own driveway.

It’s true that for certain socio-political types (like those partial to muckraking documentaries) a figure like Trump will remain an easy target of scorn. He’s the conceited blowhard whose bloated, self-titled building projects blight the old majesty of Manhattan, the condescending candidate whose first (short-lived) run for the American presidency rested on the despicable “birther” platform, the TV host of “Celebrity Apprentice” who gets his jollies watching washed-up stars like Gary Busey and Meatloaf grovel from the other side of a mahogany conference table. To a person like Susan Munro, Trump is no more than someone “with a few pounds in his pocket and a bit of a name.” The question coursing through the film is whether her outlook, serving as a great leveler when multiplied across the body politic, will win out or will more people imagine that they are just a lottery win or reality-show appearance or viral video away from joining Donald in the gentrified ranks of the 1%.

While the intrepid Baxter is tracking down Trump at press conferences and parliamentary hearings, the opponents attract a group of sympathizers who flock to a protest march and to a Trump-mocking art show held in a barn on Forbes’ farm. One of them is Mickey Foote, who in another lifetime was producer of the Clash’s first album. Now living near-by, Foote speaks knowingly about the limits of Forbes’ newfound local celebrity vs. Trump’s international stature and to what’s being lost in the deal (“a fantastic open space within reach of ordinary people.”) These scenes of citizen camaraderie may be seen as gratifying but one can only be left thinking what the future holds in an age of gaping income inequality that forms the broader background of this theme. While Trump gloats about the few hundred service-sector positions available at his resort, we’re seemingly left with an untouchable upper class run amuck in a return to a medieval-style oligarchy, with government and law enforcement in their pocket. You’ve Been Trumped smartly played out this disheartening scenario in miniature, now a more frightening version is being played out on a much bigger scale.