Plus the Rutles: All You Need is Laughs

The coolest-looking quartet ever, at the height of world domination

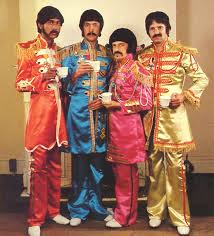

The Rutles, caught in the act of drinking tea, seen during their “Tragical History Tour”

Considering the Beatles overarching prominence in rock history, it’s a little odd that there isn’t currently available a standard-length documentary that captures their glory in any definitive sense. Perhaps this is understandable; maybe the story is just too big to be captured in one sitting. I cherish my copied-from-the-library tape of 1982’s The Compleat Beatles, a straightforward two-hour clips-and-commentary doc narrated by Malcolm McDowell. This thoughtful, soup-to-nuts approach makes for an impressive, single-volume encapsulation of the band’s legendary success in both artistic and commercial terms. Unfortunately, after its theatrical run and a successful release on videocassette it sort of dropped from view, remaining unreleased on DVD and relegated to spotty-quality ten-minute chunks on YouTube.

It could be said that 1995’s Beatles Anthology, a 3-part television special, supplanted the need for the less in-depth “Compleat”. The Anthology series does have a lot going for it, especially extensive interviews with the then three surviving Fabs. It also had a serious case of the recently discovered Ken Burns Syndrome, clocking in at 683 minutes. That may have been heaven on earth for Beatlemaniac bingers, but for the lean and mean younger generations (millions of whom have an instinctive inclination to love the band as we boomers did) this is about 583 minutes too much. Maybe some sort of updated variation on “The Compleat Beatles” will eventually see the light of day. It is important. John, Paul, George and Ringo are a shining example of creative striving and inspired collaboration. It’s also a sublime lesson in how to affect societal change using a light touch, and that being rebellious does not have to mean being revolting (yes, we’re pointing fingers at you, Mr. Beiber and Ms. Cyrus).

The Compleat Beatles–Now available on VHS from Amazon for only $41.95

It may be that 1964’s A Hard Day’s Night will end up being the best real-life record of their initial career peak, seeing that director Richard Lester smartly chose a pseudo-doc style that mirrored the Maysles Brothers’ What’s Happening! The Beatles in the USA shot on the band’s epoch-making American visit just weeks before Lester’s cameras started rolling. (Almost exactly a half-century ago. See my previous post for details!) Of course, there were also documentary cameras running during the turmoil that pointed to the band’s break up in 1970. Yet if it weren’t for bootlegs and the InterWebs, little would be seen nowadays of Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s Let it Be. McCartney and Starr show little inclination at this late date to re-air the group’s dirty laundry, although a lot of the worst of it was left on the cutting room floor. Despite the uneasy vibe and Yoko Ono’s divisive presence in Lennon’s corner of the soundstage, there are gratifying moments from the Jan. 1969 filming—an electric studio performance of the bittersweet John/Paul valedictory “Two of Us” and of course the oft-imitated rooftop concert, as London pedestrians crane their necks trying to get a last look at the world’s most famous rock band playing live.

With Compleat Beatles out of print, maybe the current front-runner as the best one-sitting Beatles film bio is—wait for it—The Rutles: All You Need is Cash. This 1978 satire began a few years before as a skit on a UK television show by Monty Python alum Eric Idle. When he hosted Saturday Night Live in ’76, he brought the clip (the gag where Idle as onsite narrator finds the camera van pulling away from him) to air on the show. Idle teamed with SNL producer Lorne Michaels and director Gary Weis (whose short films were a staple of the show’s early days) to virtually invent the rock mockumentary with their wickedly funny film about Dirk, Nasty, Stig and Barry—the alternate-universe moptops whose “legend will last a lunchtime.”

With Idle playing the hapless presenter (as well as the Paul-like Dirk) All You Need is Cash is just as much a spoof of the documentary form as it is of the Beatles. Often showing up at the wrong locale or getting nowhere with certain interviewees, he still manages to tell the entire tale of the Pre-Fab Four. Completing the Liverpool chapter after catching up with his van, he takes us to Hamburg, where the Rutles learn the ropes playing dodgy, red-light district nightclubs on Hamburg’s Reeperbahn (“the naughtiest street in the world”). That’s followed by segments on their great success in America (including their record-breaking concert at “Che Stadium”), their experimentations with tea (endless pots of it) that led to such way-out records as “Sgt. Rutter’s Darts Club Band” (“a millstone in pop history”) and onto their final works, “Shabby Road” and “Let it Rot” which was “released in 1970 as an album, a film and a lawsuit.”

Fun fact: The Rutles rooftop performance was so bad they got arrested.

As you can tell, the Rutles saga is chock full of that dry Flying Circus wit, livened by the sharp performance of Python sidekick Neil Innes as the Lennon-like Nasty. Innes, ex of the Bonzo Dog Band, composed the many spot-on song parodies, doppelgangers like “Ouch!” (Help!), “Piggy in the Middle” (I Am the Walrus) and “Doubleback Alley” (Penny Lane). It’s remarkable how the slightest sardonic twist can transform real-life musical legends into a band of incompetents. This does lead to some lapses in logic—could these goof-offs really sell out Che Stadium? But it’s the conspiratorial allowance to have a bit of fun with our cultural icons, and recognize the tendency to place them a little too high on a pedestal, that in the end shoots their stock value even higher.

And what of the band’s reaction? John apparently loved the Rutles and refused to return the preview tape he was given. One can imagine his secret delight at the film’s scenario of having Nasty hook up with destructo-artist Chastity, “a simple German girl whose father invented World War II.” Ringo reportedly loved the scenes set in the salad days, but not so much the parts that skewered the band’s messy dissolution. Paul’s reaction was pretty frosty but he may have come around when wife Linda became a Rutles fan. George of course was a big Monty Python supporter and even appears in the movie, playing a silver-haired reporter who interviews Michael Palin as an executive of Rutle Corp. (i.e. Apple) who assures us that everything is A-OK with the group’s finances even as thieves empty out the offices in the background. People with fond memories of the first incarnation of SNL will also enjoy the cameos by John Belushi, Gilda Radner, Bill Murray and Dan Akroyd.

The recent Blu-ray release The Rutles Anthology includes the decent 2005 sequel Can’t Buy Me Lunch. This 56-minute follow-up fleshes out the Rutles Apocrypha with outtakes from the first film and includes some amusing new bits like the ongoing routine where Eric Idle’s presenter faces competition from a microphone-stealing Jimmy Fallon. But as where “All You Need is Cash” featured droll testimonials from Mick Jagger and Paul Simon playing themselves, here we get the likes of Gary Shandling, Russell Brand and Tom Hanks rambling on witlessly (and redundantly) about how much the Rutles meant to them. It only serves to emphasize what the project was originally poking fun at. This mockumentary thing can be a tricky business