(A series of occasional posts hearing out the solo excursions of rock history’s supporting players whose breakaway efforts never amounted to a high-profile solo career.)

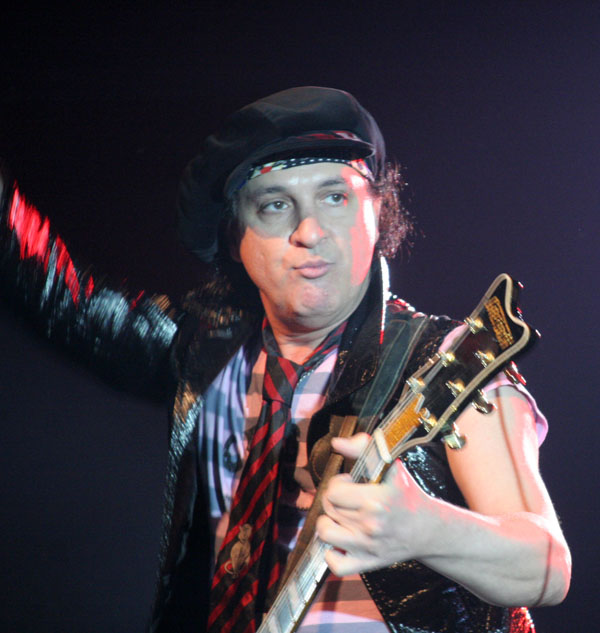

Someone like Syl Sylvain is an ideal embodiment of this series. This plucky rock ‘n’ roll survivor was a founder and second guitarist of the New York Dolls, the seminal urban-rock band who, in the time-honored tradition of pop pioneers, went under-recognized in their own time only to become beloved cult icons later. It was in lower Manhattan in the pre-gentrified early Seventies, that Sylvain met his eventual bandmates. The Dolls did a lot of the groundwork for the punk and alt-rock paradigm that followed with their swaggering rhythms, streetwise lyrics and outrageous fashion sense. Sylvain, however, was destined to be overshadowed by junkie figurehead Johnny Thunders on lead guitar and by flamboyant singer David Johansen. This despite being the group’s reliable riffmeister and, with his earlier background in fashion, a likely influence on their famously glam, drag-influenced image.

Syl was born Sylvain Mizrahi in Egypt in 1951, but anti-Semitism led his family to emigrate when he was still a boy, eventually settling in Queens. He kept his shit together through the Doll’s tempestuous tenure, while the hard-drug scourge claimed original drummer Billy Murcia in 1972 and eventually Thunders, who died in sordid circumstances in 1991. When the original incarnation of the New York Dolls flamed out in 1977, Sylvain said he felt like “the Dolls left him” and that eventually there would be a more stable second act. He had enough cache to be able to record a solo album for RCA, released in 1979.

Like a lot of would-be breakout solo efforts in this series, his self-titled album was a likable work that deserved a better break. Non-frontmen have a steeper hill to climb, and even though Sylvain is very adept at mining the Dolls’ key influences (50s rock, tender Brill Bldg. balladry, street poetry), he still can’t overcome his core value as a role player. This three-song sampler does show what fans were missing and makes the case of Sylvain Sylvain as a cool party record for those hipsters in the know.

In the Eighties and beyond there were the expected various projects that never quite panned out (the Ciminal$, the Teardrops) until the long-awaited Dolls re-union came about in 2004 when Sylvain rejoined Johansen (and for a brief time before his death from leukemia, original bassist Arthur Kane) for a festival appearance and then as an ongoing concern. They have released three pretty good albums since 2006 and toured all around, delighting the old-timers and younger fans who didn’t have a chance to see them first time around.