The third entry in my series on the wild and wondrous world of rock’s double albums.

by Rick Ouellette

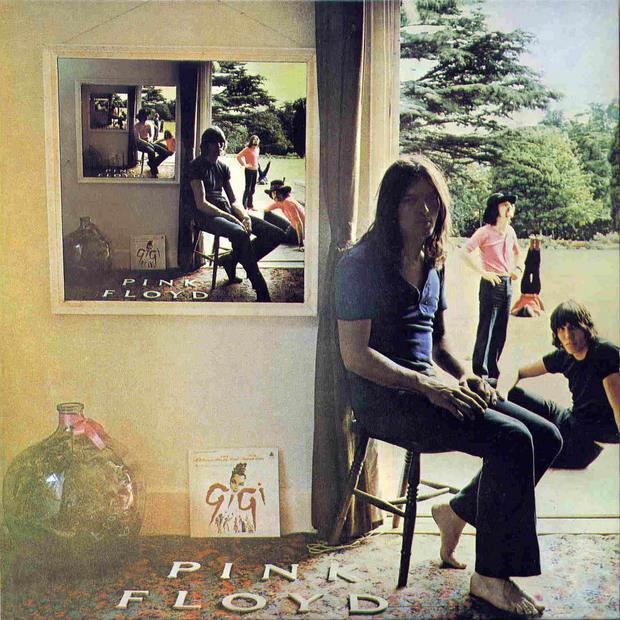

Pink Floyd at the end of the Sixties was very much the band in flux. In 1968, singer-guitarist and founding visionary Syd Barrett left the band and after an abbreviated solo career was hardly seen in public before his death in 2006. Barrett’s fanciful compositions had dominated their classic ’67 debut, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, but he barely appeared on the follow-up (A Saucerful of Secrets) and soon retreated from London to the group’s original home base of Cambridge. Beset by mental health problems complicated by prodigious LSD use and unwilling/unable to play the rock-star card for more than a few hands, the secluded Barrett would become one of music’s most fabled figureheads. Few at the time would have doubted the talents of his bandmates: bassist Roger Waters, keyboardist Rick Wright, drummer Nick Mason or guitarist David Gilmour, a boyhood friend of Barrett who joined the band shortly before Syd exited. But absent the primary writer of one of rock’s psychedelic masterworks, Pink Floyd struggled for a revised identity. After producing the soundtrack for the French hippie film More, Floyd ended the decade with the double LP Ummagumma, the type of project that would defy release today. Exploiting the era’s trend towards heavy acid jams (on its live disc) and openness to experimentation (in the studio half), Ummagumma was popular enough (#5 in the UK) to keep the band’s profile high before they hit their stride and became rock music titans with their all-world headphone classic, 1973’s Dark Side of the Moon.

On Piper, Barrett’s delectable mix of childlike whimsy and foreboding fairytales had been balanced out by two seminal excursions into what would be called space rock. One of youth music’s first extended pieces, the nine-minute “Interstellar Overdrive” was well-explained by it’s title. The other, “Astronomy Domine”, starts the live disc in an expanded version that ably states the new line-up’s mode of attack. The increased amplification of the instrumental excursions and Roger Waters’ eerie replication of Syd’s planetary roll call emanating from “icy waters underground” upped the ante of the original for the tuned-in provincial punters in the audience. “Careful With The Axe, Eugene” is transformed into a real horror show of tension-and-release, with its stalking build-up yielding to Waters’ ungodly screaming and Gilmour’s slasher guitar work. The live disc is rounded out by “Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun” and the title track from Saucerful, now a 13-minute ramble through a psychedelic funhouse led by Nick Mason’s propulsive drumming.

Giving each band member a half-side to go freeform in the studio was an early example of the self-important tendencies of ambitious acts, or maybe it was just lack of new material. The underrated keyboardist Richard Wright contributes “Sysyphus Parts 1-4” an effectively doomy piece of program music that depicts the hapless mythological character, usually spelled Sisyphus. He, of course, is fated to forever push the same boulder up a hill—probably the exact feeling Floyd roadies got during the mammoth tours in the decades to follow (the album’s back cover shows two of them with the band’s gear spread out on an airport runway).

Abandon ye all hope, the road crew that enters here.

David Gilmour’s folksy acoustic guitar on “The Narrow Way” prefigures what Jimmy Page soon was getting at on Led Zeppelin III and the vocal part that follows presages the musical heights later attained on “Comfortably Numb”. Nick Mason never had a songwriting credit before Ummagumma and after hearing his aimless percussion workout, one could be forgiven for wondering where the writing was in this case. The only track that sinks lower is “Several Species of Small Furry Animals Gathered Together in a Cave and Grooving with a Pict,” a Roger Waters’ toss-off that sounds just like its title, which should be warning enough.

Less than the sum of its “parts”?: The back of the CD 2 breaks down the multi-sectional nature of the studio disc.

Luckily, he also offers up “Grantchester Meadows,” a lovely pastoral number named after a real greensward in the band’s hometown. One of the greatest of Floyd’s lesser-known numbers, simple acoustic guitar and looped sound effects of bird tweets cushion Waters’ softly sung boyhood idyll that’s tempered by the realization that this a memory recalled from the confinement of his “city room.” The profound disatisfaction with the vicissitudes of a cold modern society, merely hinted at here, would become the primary aspect of Pink Floyd’s art in the decade to come, culminating in their other double album, 1979’s The Wall, where the confined character is not just shut off in a solitary flat, but in an enormous brick prison of his own making.

If you like the in-depth writing of rock music, both on record and on celluloid, please check out my book Rock Docs: A Fifty-Year Cinematic Journey now available. You can sample a 30-page excerpt by clicking on the book cover image at the top right of this page.