Big Charity

Directed by Alex Glustrom–2015–63 minutes

The French Quarter may have survived the 2005 devastation brought on by Hurricane Katrina, but some of New Orleans’ poorer neighborhoods, like the Lower Ninth Ward, were not so lucky and never fully recovered. The greatest institutional loss for the city, especially for those sections of town, had to be the historic Mercy Hospital. Its last iteration was the handsome and hulking Art Deco behemoth that was located downtown just two blocks from the Superdome. The hospital’s forced closing after sustaining relatively minor damage during Katrina, and the larger social implications of the shutdown, is the story of this thoughtful and quietly indignant film.

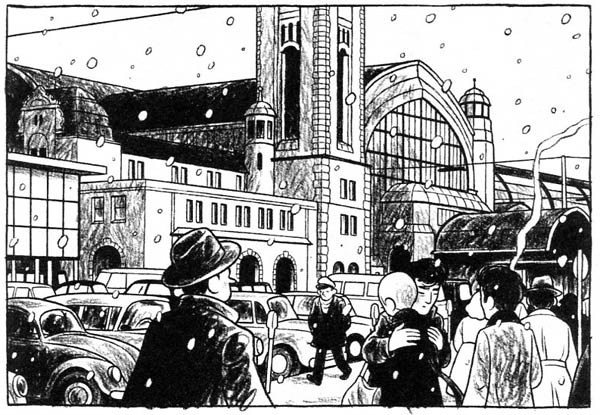

A lot can be known about Charity Hospital simply by looking at its name. The 1940 building that now stands abandoned was preceded by several others, dating back to 1736. It was founded by a French shipbuilder who stipulated a beneficent institution for the poor in his will. It kept up that model straight into the early 21st century in the giant 1939 building raised by taxpayer money and operated by the Daughters of Charity in their distinctive cornettes. With its crazy-quilt egalitarian alliances and 2700 beds, Big Charity (as it was commonly known) was not only an invaluable local resource, but the safety net hospital for the whole state of Louisiana. The building featured inspirational phrases inscribed in the lobby (“Where the Unusual Occurs, Miracles Happen”) and idealistic New Deal friezes; even it’s layout, with two extensive projecting wings resembling arms in an embrace, seemed to suggest its ages-old benevolence.

But the ad hoc coalition of community goodwill, government largesse and the nunnery was bound to be strained over a long period of shifting economics and the gradual gentrification of health care. Big Charity was eventually subsumed by the nearby Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. The hospital that stayed afloat through the Antebellum era, the Reconstruction and the advent of modern inner-city poverty, would get sunk by the notion that such places now need to be “destination facilities.” The catalyst for Charity’s demise was Katrina. Director Alex Glustrom excels in mapping out the discouraging chain of events at the hospital during the late August ’05 hurricane and the suspicious aftermath. Katrina was strong enough to shake the gargantuan building but aside from a severely flooded basement it seemingly escaped the worst.

But while Charity may have survived a Category 5 cyclone, it was no match for the institutional power play that came next. While caregivers scrambled to provide critical services without power, evacuation helicopters bypassed Charity, in more ways than one. By alternating the recollections of doctors, nurses and support staff with news footage and home video shot on the scene, Glustrom re-constructs a distressing portrait of the hospital’s sudden and shocking marginalization. Even more saddening, in the bigger picture, is the on-camera testimony of military officers whose men and women then came in and helped with evacuation, pumped out the basement and did a fix-up job on the facilities post-haste. But when they reported to LSU that the building was all ready to be re-booted they were flatly told there were no plans to reopen it.

Charity was shut up tight and its critical services unceremoniously moved to a tent city inside a closed shopping mall (the archival footage making it seem, depressingly, like a Third World scenario). Meanwhile, the old building was mysteriously infiltrated by a group of people who methodically “scuttled” the facilities. When the federal disaster relief payoff came it was a half-billion bucks for a new mega-health center, even though a modern rehab of Mercy Hospital would have cost a fraction of that. And so it goes.

Of course, reasonable people could disagree on whether or not a state-of-the-art new facility would be a better value in the long run. The more crucial issue is the overbearing influence of mega-institutions of the 21st century getting their way in every situation. The contrast between the quiet compassion of the Charity caregivers vs. the bloodless bottom-line certainties of the LSU administration is chilling. At the top of this too-big-too-fail pyramid is the Health Sciences Center chancellor, Dr. Larry Hollier. In a USA drifting towards a you’re-on-your-own default mindset, with a president well-known for his personal perversions and general heartlessness, this is the “nice” face of a screw-you philosophy.

Hollier politely tells us the LSU center is “moving away from indigent care.” as if that will solve the problem of indigence. The bulldozing of several blocks of the adjacent Mid-City neighborhood, to make way for the new complex, is termed an “inconvenience.” (This includes the demolition of many homes rebuilt post-Katrina). While Mercy Hospital remains a giant ghost shell of a building with many tales to tell, its walled-off impersonal replacement is now in place and there was no way it was going to carry over the old name. The word charity nowadays is seen by people as a “stigma” declares Dr. Hollier. Based on what I’ve seen in this moving documentary, I think a clear majority of New Orleans residents would disagree. If the doctor wants to find a person who believes that statement, he can start with a look in the mirror.