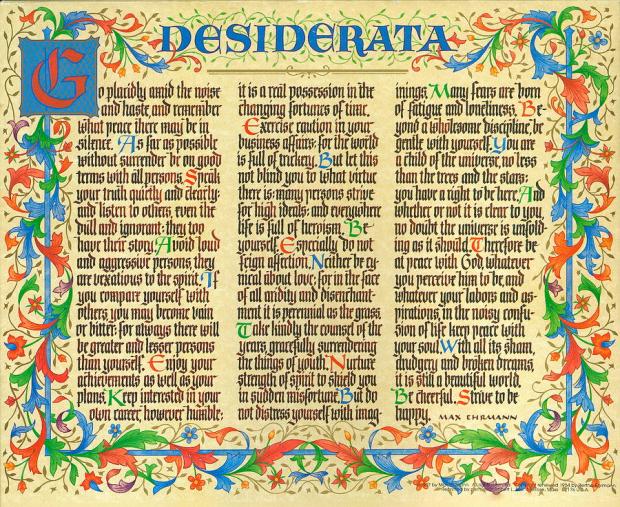

A certain little inspirational prose poem, which was born (if not completed) 100 years ago, has a few fascinating backstories. Authored by the Indiana writer Max Ehrmann (1872-1945) “Desiderata” been a touchstone of plain-spoken revelation for untold thousands, if not millions, of folks worldwide. Much of its popularity comes from the 1971 hit recording narrated by Les Crane (more on him in a minute) and featuring a soaring choir that assured one “You are a child of the universe.”

Even the origin of this famous work was once shrouded in a mystery born of a misunderstanding. In 1927, Ehrmann registered his poem for copyright but only included the first phrase “Go placidly amid the noise and the haste” adding only an “etc.” Although there would be further attempts to secure a proper copyright (esp. by Max’s widow after his death), there were lapses along the way and the “Desiderata” (in Latin, “things desired”) fell into the public domain around 1960. That is about the same time that St. Paul’s Church in Baltimore included it (unattributed) in a booklet of inspirational works. Someone took the listed date of the church’s founding, 1692, as the date of composition, suddenly giving the 35 year-old work the gravity of an newly discovered masterpiece of the early Enlightenment. This may also be why so many of the “Desiderata” posters that adorned college dorm walls used Gothic-type fonts.

A Desiderata mis-attribution on a radio survey from October of ’71. Still, it would prove way more popular than the other two new releases.

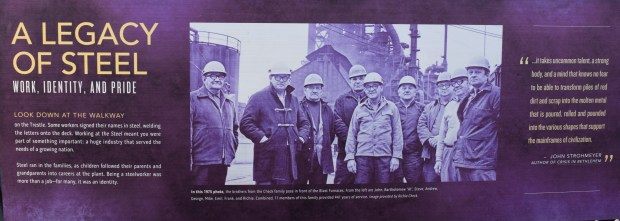

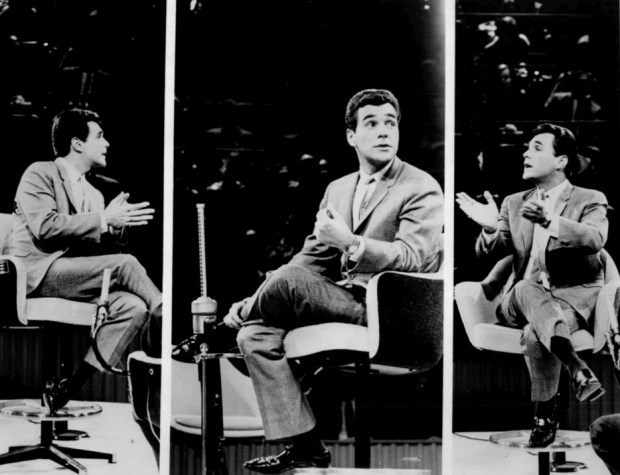

Of course, the poem’s popularity skyrocketed with the hit record in ’71. In a way, Les Crane may have been an odd MC for the record’s proto-New Age platitudes, asking us to “remember what peace there may be in silence.” He made his name in 1963-64, as a semi-controversial late-night TV host, being one of the first to try and go up against Johnny Carson. His show featured risk-taking political debates, unusual guests (Lee Harvey Oswald’s mother) and his signature shotgun microphone which he used to get hot takes from people in the audience. He was also a civil-rights advocate, respectfully interviewed both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King and had one of the first openly gay guests on TV (Randy Wicker). To cap off his Sixties’ bona fides, Crane was also married at the time to actress Tina Louise, who played Ginger on “Gilligan’s Island.”

Les Crane on his TV show in 1964.

Les Crane on his TV show in 1964.

With Crane’s portentous, deep-toned narration and the unsubtle female chorus, “Desiderata” may sound a little hokey 50 years on, but Ehrmann’s sensible, Middle-American wisdom is needed now more ever. Many may think that given the events of recent history it is all but impossible to “avoid loud and aggressive persons” who “are vexations to the spirit.” And while I am personally referring to an orange-haired monstrosity who was until very recently the U.S. president, there is good advice here on both sides of the political aisle. People who loathed Trump are aghast at his followers who have distressed themselves with “dark imaginings.” Yet they may also try and understand that “many fears are born of fatigue and loneliness” and not just react to this phenomenon with the same rigid animosity that it unleashed. As hard as it my be in the deafening world of 24/7 news cycles and ubiquitous social-media indulgences, I believe it is still of great importance to try to “speak one’s truth quietly and clearly, and to listen to others.”

Crane’s record reached as high as #8 on the singles chart and won a Grammy in the Spoken word category. Les had thought, as did many back then, that the words had been passed down thru antiquity. When he found out otherwise, Crane (who died in 2008) did the right thing and paid royalties to the Ehrmann estate.

Given the record’s grandiose arrangement, it should be of no surprise that a “Desiderata” parody would follow, and a year later the incorrigible cast of characters at National Lampoon happily obliged with “Deteriorata” from their pop-culture spoof album called “Radio Dinner.” These two records together should convince a thin-skinned world that it is both possible to have ideals and a good subversive laugh in the same lifetime. The Lampooners (the female singer is a young Melissa Manchester, a year before her fist solo LP) let us in on a little secret right off the top: “You are a fluke of the universe/You have no right to be here.” The music (arranged by future Spinal Tap member Christopher Guest) clings stickily to the original and they scored a coup by getting famed actor/announcer Norman “Voice of God” Rose to play the baritone announcer. In the parlance of today, wicked parodists like NL may be seen as “haters” but “Deteriorata” is also sprinkled with helpful life-coaching (“rotate your tires” and “know what to kiss, and when”) and bright-side thinking: “Be comforted that in the face of all aridity and disillusionment, there is always a future in computer maintenance.”

Not surprisingly, the Lampooners lose the plot for a moment along the way (“For a good time call 606-4311… ask for Ken”) but soon get back on track, assuring us that “whatever misfortune may be your lot, it could only be worse in Milwaukee.”

Now don’t that make you feel better? So while it is increasingly difficult to “Go placidly amid the noise and haste” it’s not impossible. And whether you prefer earnest inspiration or wicked satirical humor, use what you need to get there. Because even if (as NL would have it) “the universe is laughing behind your back” there is no reason why you can’t turn around and laugh right back.