(Just caught another view of this film as it is the newest entry on PBS’ “Independent Lens” series. Check your local listings as they say and see a postscript I just added below with other Detroit-related items. Rick)

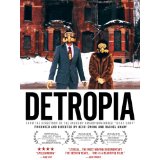

Detropia

Directed by Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady—2011—91 minutes (Docurama DVD)

The fastest growing city in the world circa 1930 is left with 100,000 abandoned houses or empty lots less than a century later. A pioneer of heavy industry and worker empowerment is relegated to being the poster child for a national trend that saw fifty thousand factories close in ten years, leaving behind a permanently insecure labor force. The home of Motown and a mighty civic infrastructure reduced to the outward appearance of a fallen civilization. Few places illustrate the diminished American Dream better than Detroit. The documentary filmmaking team of Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady (who also made the excellent “Jesus Camp”) grapple with this weighty subject with a blend of citizen testimonials and impressionistic visuals, gleaning both the ground-level personal perspective and the dreamlike aura of an oversized ghost town.

Soon after the opening lament by video blogger Crystal Starr, as she gazes at the Motor City skyline from the upper story window of an abandoned apartment building, the film gets right down in the business. United Auto Workers official George McGregor regales the interviewer with stories of past glories while driving to a union hall meeting where most of the chairs remain stacked in the background of the shot. The nearly depleted rank-and-file membership listen in disbelief as McGregor reads out the latest proposal by American Axle, a company already threatening to move its production out of the country. Faced with either accepting a pay package that will leave them with slightly better than fast-food wages, or seeing the same jobs shipped overseas with impunity, it’s hard to leave the scene without understanding why the American middle class seems as gutted as the deserted buildings we see in so many of “Detropia’s” establishing shots.

Elsewhere, we see a nightclub owner trying to hang onto his business in the face of plant closures and fretting at an auto show when he sees the Chinese poised to corner the electric car market; briefly meet a performance-art couple attracted to the city’s low housing costs; and hang out with some enterprising metal scavengers, picking at the carcass of a once-great metropolis and selling the scrap to a country that can use it (China again). For Mayor Dave Bing, the options for improving conditions in this broke city are few. Left with half the town that once was, Bing (a former Detroit Pistons basketball star) proposes consolidating the thinly-spread population—down to 700,000 from a mid-century high of 1.8 million—into higher-density areas while “re-purposing” vacant land for large-scale urban farming. This idea is met with skepticism at a tumultuous community meeting and by a trio of amused front-porch philosophers. It’s these regular folks that make “Detropia” as appealing as it is, counteracting the directors’ tendency for a grab-bag approach that can cause contextual drift. So even amid the ghostly greens and reds of nocturnal street scenes, or snippets of barely-introduced subjects like the African-American opera singer, there will soon be some level-headed resident, with that Motor City mix of gallows humor and dogged perseverance, to keep things grounded.

In the end, several of the subjects sneak their way into the city’s gargantuan Michigan Central Station, the long-vacant Beaux Arts masterpiece that as much as any one edifice symbolizes this epic fall from grace. While the strategic bailout of the auto industry engineered by President Obama offers a modicum hope, the outlook remains bleak. The city went under state receivership in early 2013 and Dave Bing decided not to run for re-election. While there may be no foreseeable turnaround for the city’s endemic woes, to treat this as a matter apart from us is inadvisable in the extreme. “When you see your neighbor going down, you have to think about yourself,” the club owner warns us in the waning moments of “Detropia,” adding “a fire unchecked will only take you out as well.” It is another reminder of America’s abandonment of a production-based society in favor of an economy dependent on a distracted consumerism many can’t afford and lorded over by esurient Wall Street CEOs rewarded for cutting workforces. Ewing and Grady are to be commended for making their accessible and heartfelt film on this discouraging subject.

One thing I would have liked to seen a little more of in “Detropia” is the astonishing scale of both what was built there and the extent to which it has fallen to ruin. If you’re like me, then, check out the book “Detroit Disassembled”. I mean that literally. Check it out of the library if you can’t afford the hefty price tag, even if photographer Andrew Moore deserves every penny of it. This is one of the most extraordinary photo-essay coffee table books I’ve ever seen. Moore’s large-format camera peeks into every conceivable corner of what, through his lens, might as well be a lost ancient ruin. A melancholic paen to a faded nation of makers, the infrastructure and institutions that supported this industry-based system are now seen as losing a visceral battle to decay and the forces of nature. The dilapidation of catherdal-like assembly buildings, rococo theaters, technical schools, grand theaters and handsome apartment blocks may seem like an exaggerated and isolated example to some, but it leaves behind a sour taste nevertheless. It makes one think of the pipsqueak service economy we’re left with, 70% of which is dependent on consumer spending while at the same a huge percentage of workers are making the kind of wages that almost make indentured servitude an attractive alternative.

While I’m at it, I will also recommend the 4-minute film clip link below but don’t read the caption as it contains a spoiler alert, Documenatry Division.

Godfrey Reggio’s 2002 “Naqoyqasti”, the last of his trilogy that began with the trailblazing “Koyaanisqatsi” opens with that solemn tracking shot of the Michigan Central Station’s massive vaulted waiting room and once magisterial upper-floor offices, every window now smashed. Back on the ground, a close-up of the building’s mighty portico and entrance has a raging sea superimposed over it and the effect is of all of Western culture being pulled under.

![the-shining-still-3[1]](https://rickouellettereelandrock.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/the-shining-still-31.jpg?w=620&h=430)

![shining%20boy[1]](https://rickouellettereelandrock.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/shining20boy1.jpg?w=620)