The review below taken From “Documentary 101: A Viewer’s Guide to Non-Fiction Film”

Now on sale: http://booklocker.com/books/6965.html (This author page has an extended book excerpt. Also available from Amazon and barnesandnoble.com)

The Beatles: The First U.S. Visit

Albert and David Maysles—1964/1991—83 minutes

It was only ten weeks after the assassination of President John Kennedy. With the pall of national tragedy still in the air that winter, the filmmaking team of Albert and David Maysles got a call from Granada Television in England saying a musical group named the Beatles were arriving in New York in a couple of hours and would they mind heading down and maybe getting some footage? Albert was a bit nonplussed but younger brother David was more hip to the current pop scene and sensed the opportunity. After negotiating a deal right there on the phone, the light-traveling duo were on their way to recently renamed John F. Kennedy Airport, getting there just in time for the famous moment when John, Paul, George, and Ringo hesitated a moment at the top of the steps while leaving the plane, realizing that the hordes of people lining the balcony of the terminal were there for them and not some head of state as they first thought. And just like that the Maysles brothers found themselves in the middle of one of the twentieth century’s defining cultural moments. The First U.S. Visit is a 1991 re-edit of the original ’64 film (called “What’s Happening: The Beatles in the U.S.A.”) that adds more music and excises some interview material. But both versions pull the viewer right into the middle of the tumultuous birth of 1960s youth culture. It also features the Beatles performing thirteen unedited songs, from both a Washington, D.C., concert and the epochal Ed Sullivan Show TV appearances.

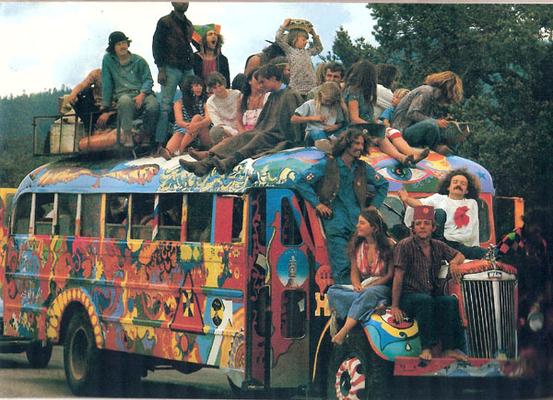

Twisting by the pool in Miami Beach, 1964

The Beatles were poised for big things and “I Want to Hold Your Hand” (their first widely distributed single in the U.S.) had hit #1 two weeks previous. Early segments show famed DJ Murray the K in his studio hyping them up but establishment media were often belittling in their opinions and their long-term prospects in America were uncertain. At the airport press conference they quickly charm the jaded New York press corps with their contagious high spirits and sharp wit, then are whisked off to Manhattan and to a rock ’n’ roll superstardom never to be equaled. Although a few hours before they had hardly heard of the Fab Four, the filmmakers found themselves squished into the back of a limo with the confident but still nonplussed band members. Arriving at the Plaza Hotel, we get the first dose of Beatlemania up close with fans pounding on the window, the boys dashing from the car to the lobby door, and the scenes of police struggling to keep back the hordes, all soon to become iconic images of the decade. Two nights later, on February 9, 1964, the band would make television history with 73 million people tuning in to Sullivan’s Sunday-night showcase. The Maysles brothers would tag along for the next five days with unfettered access and whether it’s the boys goofing around in hotel rooms, dancing at the Peppermint Lounge, or getting photographed in Central Park, the camera never seems more than a few feet away from the action.

When it’s time to head south for the D.C. concert, the whole entourage takes the train like it is no big deal and the band jovially mingles with the other passengers. The group here is shown at a giddy apex of fame just before becoming imprisoned by their own celebrity. And although the performances on Sullivan’s show seem as fresh and buoyant as ever, the gig at the old Washington Coliseum may be the musical highlight here. Playing from a makeshift stage in the middle of the arena, the group is surrounded by the deafening din of screaming girls but cut through the pandemonium with a manic energy unseen on the tube. “I Saw Her Standing There” rocks with an almost punkish jolt and Ringo gets a rare concert lead vocal during a likewise frenetic “I Wanna Be Your Man.” The sight of the four of them having to turn around their own amps and rotate the drum riser to play to a different part of the house couldn’t be quainter—roadies weren’t even invented yet!

The Beatles raise the roof on the Washington Coliseum, Feb. 11th, 1964

Ed Sullivan is waiting down in Miami Beach, ready to introduce these “fine youngsters” for the second of the three consecutive weeks on his show. Although the Maysles brothers’ time with the Beatles ended down there, also included is their return appearance (taped earlier) at the regular New York location for week three on Sullivan (with a farewell rave-up of “Twist and Shout” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand”) and a bit of their departure and triumphal airport reception back in London.

The filmmakers’ methods seem to point the way to one of rock’s most celebrated films, “A Hard Day’s Night”, which started filming a month after the group’s return. That movie’s director, Richard Lester, carefully crafted a pseudo-documentary feel and a few notable scenes, like the mob-besieged Beatles running to their catch their train before being eaten alive, were not staged but done spontaneously, a bit of cinematic verisimilitude not appreciated by the band. “What’s Happening!” (as it was still known) was a great feather in the cap for the Maysles brothers. With an eerie symmetry, these Johnny-on-the-spot filmmakers would close out the 1960s with “Gimme Shelter”, unwittingly filming the dark flip side of the scene the Beatles created while following a late 1969 tour by the Rolling Stones.