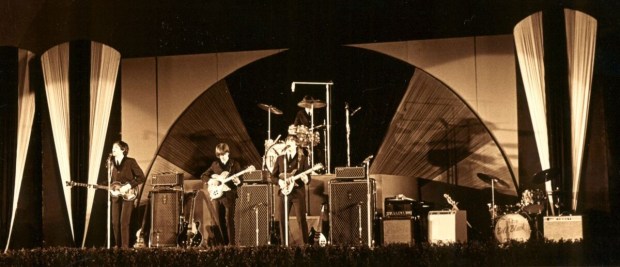

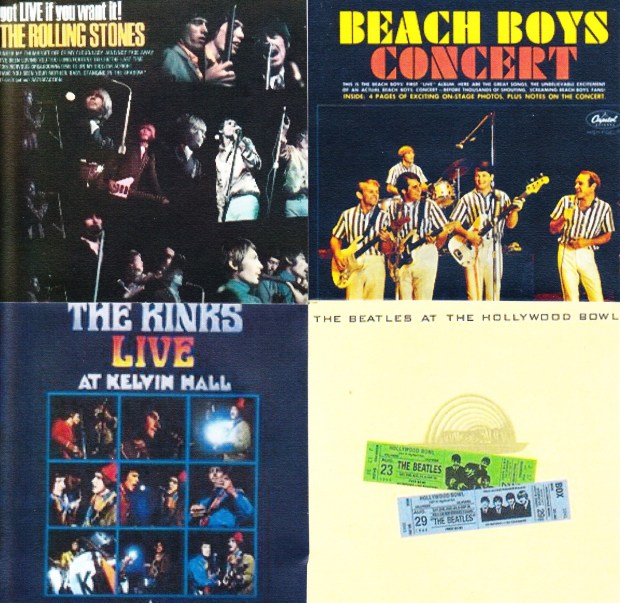

It’s a funny thing, the long tradition of rock artists recording songs written by others. The origin story of untold thousands of bands has them cutting their teeth on an old Chuck Berry number or blues standard, or maybe “Louie Louie” and/or “Gloria.” Many groups soon to be famous for penning their own tunes, from the Beatles and Stones on down, peppered their early albums with cover material. Hell, even Bob Dylan’s 1962 debut only featured two songs written by the man himself.

But from the mid-Sixties on, the only true way forward in the rock business was to be performing your own compositions. Unlike the Sinatras or Tony Bennetts of an earlier era, the pantheon of Boomer-era acts featured few song “interpreters” (Linda Ronstadt and Joe Cocker are two that spring to mind). If you can’t write ‘em, your outfit may soon be relegated to eternal bar-band status.

Yet no matter how good a band’s own material may be, musicians are always fans first. A well-placed cover song can really add to an album’s success, whether it be Jimi Hendrix’ definitive take on Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower,” the Clash’s “Police and Thieves,” the Talking Heads’ “Take Me to the River” or name your favorite.

But an album full of other’s material by those well known for penning their own songs rarely turns out to be a triumph. Is it because many are contractual obligations, or place markers when one is a little thin on new material? While some are fun, rarely is it a discographical highlight. Let’s have a look.

“Pin Ups” David Bowie (1973)

Let’s start with a good one, so we can see what makes for a successful covers album. The reason Pin Ups ranks so high is that it has a workable concept and there is an effort made on some tracks to put a new spin on the material. David gives props to the British bands that inspired him in the years 1963-67, just prior to his own recording career taking off.

He does a slowed-down version of the Who’s “I Can’t Explain,” playing a sexy sax refrain to go with it. The wild instrumental coda he gives “See Emily Play” makes it even more acid-drenched than the Pink Floyd original. True, elsewhere he sticks close to the original, as on the two Pretty Things selections and the Kinks’ great anti-anthem “Where Have All the Good Times Gone.” But these are helped by the fact that they are backed up by the Ziggy Stardust band, featuring guitarist Mick Ronson on guitar. Another highlight is Bowie’s lovely, doleful take on the Mersey’s “Sorrow” which was a hit single in several countries. Grade: A-

“Moondog Matinee” The Band (1973)

“Why don’t we just do our old nightclub act” the late Levon Helm recalled someone in the Band saying, but the drummer/vocalist can’t recall who, per his lively memoir “This Wheel’s on Fire.”

The group was in the middle of a ten-record deal with Capitol Records and short of new material. They were also in the middle of a group relocation from the Catskills to Malibu and cutting a quick record of tributes bought them some time. It’s more a well-curated and well-performed selection of early R&B and rock ‘n’ roll chestnuts than a nightclub act, though they deliver some potential crowd-pleasing things like the cheeky Lieber-Stoller rug cutter “Saved.”

Elsewhere, songs from Sam Cooke, Allen Toussaint, Fats Domino and Chuck Berry abound. There a few twists: keyboard wizard Garth Hudson has a great go at the timeless “Third Man Theme” and Helm used a then-newfangled talkbox to get the needed croaking part on Clarence “Frogman” Henry’s “Ain’t Got No Home.” A fun listen but inessential, like many in this category. Grade: B

“Rock ‘n’ Roll” John Lennon (1975)

John Lennon was well known for his deep-rooted love for Fifties music but the actual impetus for this album came from a court settlement. The notorious music publisher Morris Levy sued Lennon because the music to the Beatles’ “Come Together” (though slowed down) and one line (“Here come old flat-top”) bore a strong resemblance to Chuck Berry’s “You Can’t Catch Me,” which Levy owned. The agreement read that John would record three songs from Levy’s publishing company on his next album.

When word got out in the fall of ’73 that Lennon was recording a tribute album in Los Angeles, all his musician friends/drinking buddies showed and it was quite a scene. Producer Phil Spector shot a hole in the roof and a bottle of whisky spilled onto the console, amongst other hijinks. Some material managed to get recorded but then Spector ran off with the master tapes. Lennon shelved the project and recorded Walls and Bridges instead. The tapes were eventually recovered, and the rest of the album was knocked out (under further legal duress from Levy) in three days in the fall of 1974 for an early ’75 release.

The results were predictably patchy but there are some fine moments: an energetic stomp thru “Bony Moronie,” a reggae-inflected “Do You Want to Dance,” and a soulful take on Ben E. King’s “Stand by Me” that was a Top 20 single. Elsewhere, several tracks sound rushed or uninspired, and admittedly one of the best things about Rock ‘n’ Roll is Jurgen Vollmer’s great photo of a young, leather-jacketed Lennon leaning in a doorway from the Fab’s Hamburg years. Grade: B-

“Givin’ it Back” The Isley Brothers (1971)

Well, here’s a bit of a “twist” in the covers album scheme of things. The Isley Brothers, whose songs had been covered by many Sixties rock bands (esp. in the case of the Beatles’ “Twist and Shout”) return the favor by covering an eclectic collection of (mostly) white artists. Side One consists of three extended tracks, marching out of the gate with a powerful protest medley of Neil Young’s “Ohio” and Jimi Hendrix’ “Machine Gun.” The Vietnam War was still very much happening in 1971, and there’s no missing the urgency in Ron Isley’s lead vocal. Meanwhile, kid brother Ernie, not quite twenty at the time, gets to show off his already prodigious guitar chops. Hendrix was briefly in Isley’s backing group and his influence was quite clear on Ernie, who knew Jimi as a kid.

Turning James Taylor’s regretful ballad of a friend’s suicide into an Issac Hayes-style psychedelic soul number may not have been the best decision, but their “Fire and Rain” is interesting, nonetheless. More successful is their ten-minute slow jam on Bob Dylan’s “Lay Lady Lay” which gives Ron plenty of time for seductive ad-libbing, stopping just short of Barry White territory. (On successive albums, the Brothers would continue to produce extended soulful covers of soft-rock hits like “Summer Breeze” and “It’s Too Late,” often featuring dramatic guitar workouts from Ernie). The album rounds out with two Steve Stills’ numbers (the single release of “Love the One You’re With” hit #18 on the pop charts) and Bill Withers’ “Cold Bologna” with the songwriter guesting on guitar. Grade: B+

“Compliments of Garcia” Jerry Garcia (1974)

When I was in high school, I received a complimentary (if you will) armful of Grateful Dead-related vinyl from my girlfriend’s neighbor who worked as a publicist for the band. There were acknowledged classics (Workingman’s Dead), a few oddities (the outré soundscape Seastones on which a couple of Dead members appeared), and a few solo albums, including this covers album which for some time was a left-field favorite of mine. It presents as a record to be lightly regarded, as Jerry gives low-key props to some of his wide-ranging influences. But as soon as the train whistle and shuffling beat kicks off the album (with Chuck Berry’s “Let it Rock”), I was drawn into the record’s laid-back appeal.

Maybe it hasn’t aged all that well in this less laid-back time. His takes on Smokey Robinson and Dr. John are pleasant if unspectacular, and Garcia maybe should have second-thought the inclusion of “Let’s Spend the Night Together” (one reviewer quipped that this version made it seem like the couple in question spent the night playing cards). But there are also well-considered versions: his in-the-pocket rendition of Van Morrison’s “He Ain’t Give You None” is preferrable to the author’s undisciplined original on T.B. Sheets. Best of all is a beatific, slowed-down take on Seatrain’s “Mississippi Moon.” And it ends nicely with “Midnight Town,” an atmospheric number by Garcia Band bassist John Kahn. Grade B-

“The Hit List” Joan Jett (1990)

I was a bit surprised at how quickly this album flat-lined for me. Maybe because Jett’s breakout solo LP (1982’s I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll) featured three definitive cover tunes. The title track she made completely her own, turning it into a worldwide #1 single. Another breakout performance was on Tommy James’ “Crimson and Clover,” where her breathy, come-hither vocal memorably mixed with crunching power chords. And it ended with one of the best-ever holiday rock songs, a bratty “Little Drummer Boy” that concluded with an instrumental rave-up worthy of the Who’s Live at Leeds.

So where did The Hit List go so wrong? For one, randomness never bodes well—Jett goes from ZZ Top to the Sex Pistols to Credence as if all three bands were cut from the same cloth. Secondly, her vocals range from pro forma to uninspired. She practically sleepwalks thru “Love Hurts,” only serving to remind one of the full-throated drama of Nazareth’s hit version or the plaintive charm in the way Gram Parsons did it. And strangely enough all we get is autopilot mode on AC/DC’s “Dirty Deeds,” which should have been a natural for her.

There are a couple of modest highlights. There’s the one left-field choice (the Hendrix obscurity “Up From the Skies”) and an appealing version of the Kinks Klassic “Celluloid Heroes.” Here we get the Sweet Joanie voice and a convincing arrangement that leads up to one of her patented shouts, maybe the only one on the whole record. Saved from a D+ for the glamourous cover photo. Grade: C-

“Thank You” Duran Duran (1995)

In deference to some of the selections above, being uninspired is one thing but being downright bizarre is quite another. And so we have New Wave glamour boys Duran Duran. They may have peaked in popularity in the early 80s but in the mid-90s their records were still regularly in the Top 20, esp. in their native UK. So I’m not sure what inspired them to foist this rummage sale of a covers LP on the world. Taking on vintage R&B, hip-hop, classic rock and ballads with the same dilettantish insolence, Thank You was voted the worst album of all-time by staff of Q magazine in 2006.

Probably most galling for the critics, were DD’s take on two notable rap numbers. Their Beck-like version of Public Enemy’s “9-11 is a Joke” is a joke. But it’s not as bad as the presumptuous run-thru on Grandmaster Flash/Melle Mel’s classic “White Lines.” You can’t fault the boys on their energy level but the cognitive dissonance is too pronounced to overcome. Let’s just say it’s a long way from a Bronx block party to a Notting Hill boutique.

Elsewhere, there are very unimpressive takes on oft-covered material like “Ball of Confusion,” “Lay Lady Lay” and Lou Reed’s ubiquitous “Perfect Day.” I will give bassist John Taylor props for his work on the “funkier” numbers, but singer Simon Le Bon didn’t get the memo that there is more to paying tribute in song than just knowing the words. Worst of all is a regrettable version of the Sly Stone’s “I Wanna Take You Higher” which concludes with some teenybopper girl dumbly asking the guys where they wanna take her and when they dumbly reply “higher” you realize that this giant mistake of an album couldn’t get any lower. Grade: D

More coming up soon in Part Two, including entries from the Ramones, Patti Smith, Cat Power and Elvis Costello. —Rick Ouellette