Rock and roll band names are always a fun subject and historically have fallen into specific categories. Early on, bug names were popular: Buddy Holly and the Crickets inspired the Silver Beetles (later the Beatles), and we went from Iron Butterfly to the Spiders from Mars; it all culminated in the legendary Mosquitoes, secretly rehearsing on Gilligan’s Island to escape their adoring fans.

In the psychedelic era, crazy food-related names abounded (Strawberry Alarm Clock, Chocolate Watch Band, Ultimate Spinach, Peanut Butter Conspiracy) but as we got into the 70s, the somewhat grandiose idea of naming your group after a (usually) large city, or even a country or continent, took hold. Sometimes (but certainly not always) it reflected where the group was from. This trend has continued somewhat crazily into the present, as we will find out at the bottom of the post.

But here we are mostly sticking with better-known groups from the 70s to the millennium. There is a subjective group rating and a ROBTL rating (Relation of Band to Location). Only straight-up geographic group names are considered (sorry, New York Dolls) and the locations are limited to our home planet. But in case you’re wondering, there IS a group called Uranus.

CHICAGO

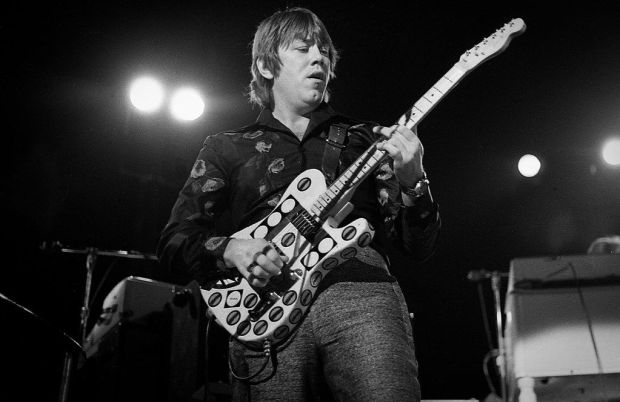

This is one of the most famous, even though they were originally called Chicago Transit Authority, until transportation officials from the Windy City objected. Many of the members from the original septet met while in college in Chicago. They were originally an adventurous, even political, jazz-rock ensemble over the course of their first three albums (all two-record sets). They gradually lost their way in the woods of MOR pop pablum after the tragic death of guitarist/guiding force Terry Kath.

Group Rating: B+ for the first five albums, after that you’re on your own. ROBTL Rating: Good, considering their roots

This track from their debut features demonstrators’ chant from the Chicago Dem Convention in 1968.

AMERICA

An interesting one, as the three members were U.S. Air Force brats living in England at the time of their formation. But their sound, influenced by the CSN&Y type sound of the day, was very un-British. They went on to great success, of course, with songs like “Ventura Highway” (inspired by a stretch of road in California) and that one about a lonesome Western desert where for some reason you can’t remember your name.

Group rating: B ROBTL: Good I guess, since it was a bit of a mission statement.

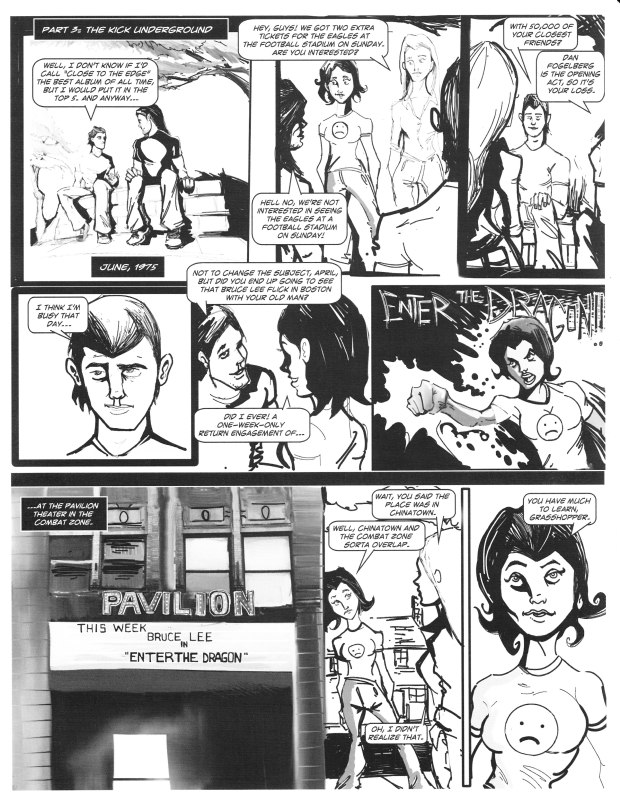

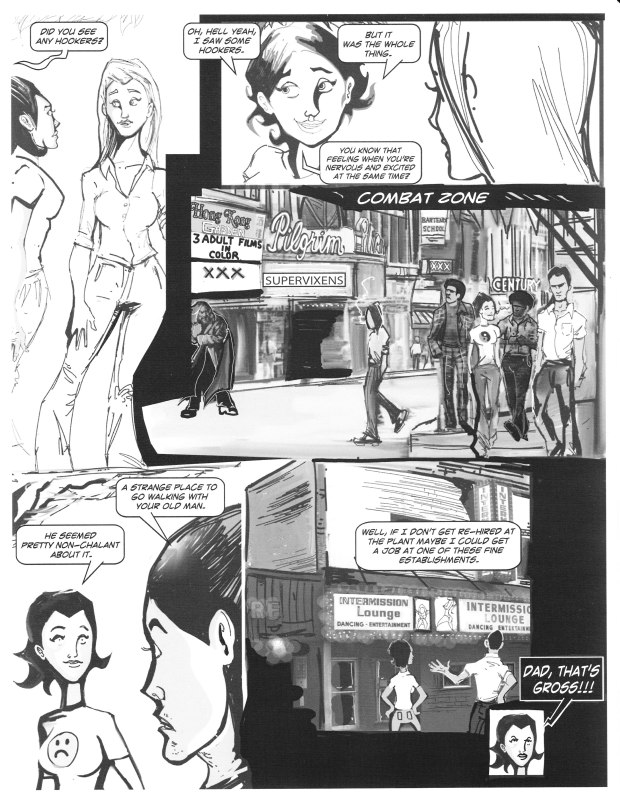

BOSTON

This Tom Scholz-invented band is a tough one, since they were from the area but were not exactly road-tested locals, like Aerosmith or J. Geils Band. Mostly a studio creation, thanks to Scholz’s whiz-kid tech knowhow, that didn’t stop them from claiming they were “just another band out of Boston” on their debut album which sold 17 million copies. Then they started touring.

Group rating: B- ROBTL: Not great, even that line about playing in Hyannis was not about them but instead was inspired by the drummer’s previous experience of playing in bar bands down on Cape Cod.

BERLIN

Crossing over the Atlantic, kind of. Berlin, fronted by icy-sultry singer Terri Nunn, was from Los Angeles. Nunn, who posed for Playboy while underage, was (and would later be) an actress, and she once auditioned for the part of Princess Leia. She had the perfect look and voice for the band’s stylish 80s synth-pop sound, which would be fair to say, drew some influence from Krautrock pioneers like Kraftwerk.

Group rating: B ROBTL: Pretty good, considering.

LINDISFARNE

This accomplished British folk-rock outfit, once led by guitarist singer Alan Hull, were from Newcastle and named themselves after the nearby monastery castle that I had the pleasure of visiting last year (see my photo!).

Lindisfarne often drew from locales known to them and it would be easy to imagine the ghostly “Lady Eleanor” from their most famous song roaming the drafty corridors of that edifice.

Group rating: A- ROBTL: First in class.

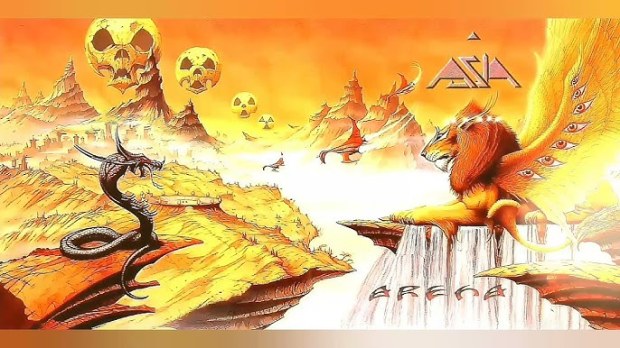

ASIA

Another very famous name and a progressive-rock supergroup made up of former (and in some cases future) members of Yes, King Crimson and ELP. I’m a huge prog fan but at the time of their big debut LP (1982) I was much more in thrall to the likes of the Replacements and the Psychedelic Furs than this machine-tooled AOR approach. Even guitarist Steve Howe, who would do much much better work in Yes) admitted that the production of said album was “Journeyesque,” not a good thing. But they fared well on middle-of-the-road rock stations and sold lots of plastic.

Group rating: C ROBTL: Nil, unless you count Roger Dean’s somewhat Oriental cover art. (see top image)

EUROPE

Staying on the continental theme, we doubt anyone ever looked to these lugs for a representation of European culture. The glam-metal Swedes did have their moment in the sun (not that I noticed) and got a recent ironic boost due to their famous Geico commercial featuring their biggest hit.

Group rating: C- ROBTL: Nothing doing.

ENGLAND

This prog-rock band was destined to be under-appreciated, seeing that their excellent debut album, “Garden Shed,” came out in 1977, the same year that the Sex Pistols and the Clash were shaking up things in their native land. England were led by keyboardist-singer Robert Webb and they hailed from Kent County, an area known as the Garden of England. Later reevaluations and rereleases of their work led to reunions (and some new work) first in 2006, including a nice 2-disc CD edition of “Garden Shed.”

Group rating: B+ ROBTL: Very high

JAPAN

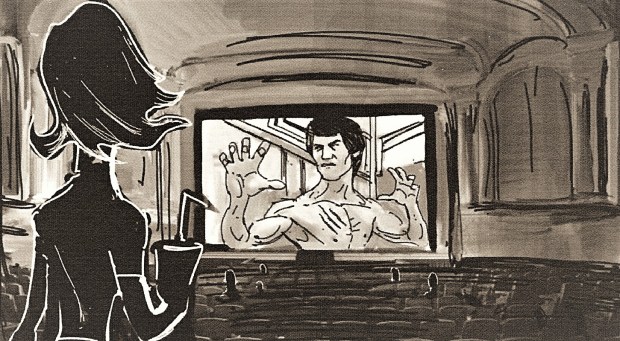

This London-based group started out in 1974 as more of a glam act and evolved a synth-heavy, futuristic approach in the New Wave era. Not my cup of tea and initially their records flopped in the UK, but they found fame in the Land of the Rising Sun. Not sure how much that had to do with their name. They did release a single called “Life in Toyko” but it oddly featured the catch phrase “life can be cruel.”

Group rating: C+ ROBTL: Well, they sold out Budokan three nights running.

NEW ENGLAND

Getting back to my neck of the woods, this Boston-based group was managed by Queen impresario Don Aucion. They got a peek at the Top 40 with “Don’t Ever Wanna Lose Ya” (#40 in 1979) but their career soon stalled. Although stubbornly a product of their Asia-Journey age, New England did poke at the edges of several genres, including Art Rock. Seeking a sales lift, they came up with the multi-part “Explorer Suite.” Brimming with dramatic vocals and flashy keyboards, they were hoping the “Bohemian Rhapsody” lightning would strike twice, but to no avail.

Group Rating: B- ROBTL: Nothing you would notice.

NANTUCKET

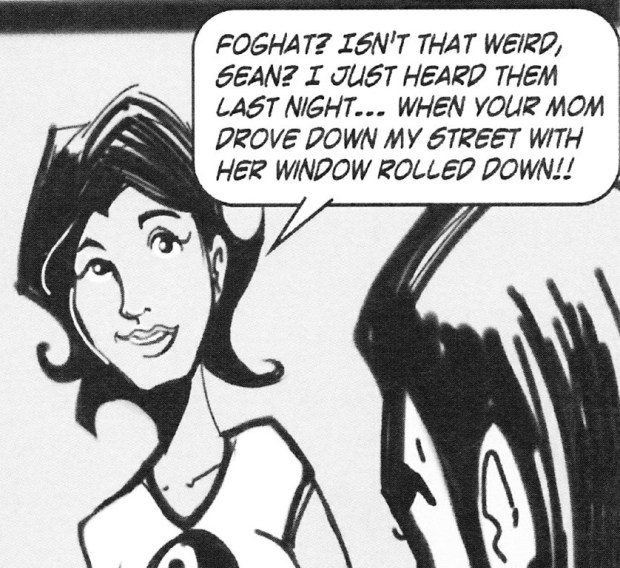

Another New England locale, but these guys were from North Carolina and got their start as an oceanside bar band. They named themselves after the song “Nantucket Sleighride” by Mountain. There is some of that influence here, but also of arena-rock plodders like Foghat. Nothing special but I like their energy and the cheeky covert art of their first album is a 70s guilty pleasure.

Group Rating: B ROBTL: Very little.

KANSAS

I really don’t want to talk about these guys. You know them, you love them. Well, you know them anyway. Me, I always get them mixed up with Styx, another location-named band, though in this case a presumably fictional one. Anyway, I don’t dislike them, but I don’t regard them either. They did find a curious common denominator in pop history. “Carry On My Wayward Son,” is annually one of the most played song in classic-rock radio formats.

Group Rating: B- ROBTL: Well, they are from Topeka.

MANASSAS

I don’t much want to talk about Steve Stills either. He’s one of rock’s least likable characters. If you care for a taste, consult the interview of jazz drummer (and one-time Joni Mitchell squeeze) in the book “Girls Like Us” or check out Steve’s belligerent reaction to a little healthy criticism in the festival film “Celebration at Big Sur.” Having said that, Manassas (named after the Virginia town where the first great land battle of the civil war took place) were a good band for him, esp. in the case of second-billed Chris Hillman, the reliable wing man late of the Byrds and Flying Burrito Bros. Their first album was one of Stills’ stronger efforts (and a double LP no less) and I’ll be happy to post my favorite track.

Group rating: B ROBTL: Well, it is kinda country rock.

CHILIWACK

Chiliwack’s 1971 single “Lonesome Mary” was one of my favorite obscure near-hits of my early radio-listening days I remember the DJ telling listeners that the group was from Canada, and so far north there that there “drummer is a grizzly bear.” They were actually from Vancouver and named themselves after a cool-sounding town nearby. “Lonesome Mary” was one of those killer 3-minutes slabs of power rock, with Bill Henderson’s urgent vocals and blazing guitar.

Later, Chiliwack dabbled in progressive rock, which was still evident in their 1979 album “Breakdown in Paradise” which I picked up on cassette in a Quebec City shop last year. In the early Eighties, they got their commercial due with a few poppier U.S. Top 40 hits, most notably with “My Girl (Gone Gone Gone)”, and are still a going concern these days.

Grade: A (just because) ROBTL: Grizzly bear or no grizzly bear, they representing!

The geo band phenomenon continues to this day, although reading up on the subject can cause confusion. There’s an Indiana band called Brazil but formerly called themselves London. The group Spain are from California, and Jamacia are from France. That’s not even mentioning the ones named after planets and constellations, though I do want to check out Uranus, lol.