I come to praise Cesar (Catalina), not bury him. For many, “Megalopolis” is an easy film to dislike, but it’s a rewarding one to give an honest look at. Francis Ford Coppola’s long-gestating mega-project is messy and often unfocused, with moments of unintentional hilarity. But those moments are not nearly as laughable as some of the negative opinions lobbed at it.

In an age where cynical slasher movies and DC/Marvel sequels are puked off a cinematic assembly line at record pace, calling “Megalopolis” the “worst movie of all time” with “no redeeming qualities” is kind of like settling on Milli Vanilli’s “All or Nothing” as your favorite album because you thought the Beatle’s “White Album” was too sprawling.

In a re-imagined New York City called New Rome, superstar architect Cesar Catilina (Adam Driver) has altruistic ideas for rebuilding a city that is a teetering empire very obviously based on its namesake. Against a backdrop of garish decadence (there are orgy-like parties and even a chariot race) Cesar’s proposal, as chief of the city’s Design Authority, is opposed by the old-school mayor Franklyn Cicero—played by Giancarlo Esposito who bears a strong resemblance to NYC’s current embattled mayor Eric Adams.

In its own loopy way, “Megalopolis” is a sincere plea for an idealistic way forward for a world society in a time of debilitating tribal and nationalistic divisions. Comparing the bitterly polarized America of today to the approaching fall of the Roman Empire is not exactly a novel idea, but Coppola’s visual representation of this concept is the film’s strongest element.

From the late 19th century to the mid-1940s, New York was built to a majestic, inspirational scale comparable to what the Eternal City was in the ancient world. Cesar’s apartment/studio is in the defunct Cloud Club atop the Chrysler Building. Imposing low angle views of the Helmsley Building, Grand Central and other classic Manhattan structures are used to great dramatic effect, and we get to go underground to get a glimpse of the faded glory that is the old City Hall subway station. Colossal living statues sit despondently or crumble in alleyways, their great allegorical symbolism forgotten.

At the core of “Megalopolis” is a factor often overlooked but important enough to warrant its own section in the movie’s Wikipedia entry: “Artistic Idealism as Antidote to Polarization.” That is, the role of the creative class in helping create more inclusive and livable cities. I can only hope that Coppola’s vision at least inspires some younger artists to foster a new generation of bold, humane visions (and in all the various ways they can be attained) in a world that so surely needs it.

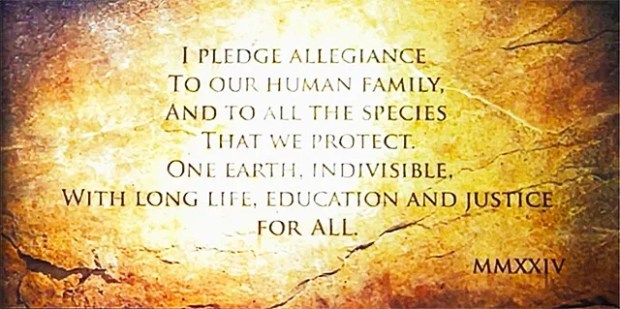

The film’s closing title card attempts to transcend both nationalism and identity politics.

I did, however, have a problem with Cesar Catalina’s use of the word “utopia” which Mayor Cicero correctly identifies as a fantasy land. What Cesar really strives for is a “protopia,” a practical way forward to a better world for all. I think it was a deft move by Coppola to have the cerebral Cesar allied with the more grounded mayor for the film’s corny but uplifting closing scene.

Hopefully, this noble-but-flawed valediction for the 85 year-old filmmaker will outlast the confidence of the naysayers who to me sound too smart to know any better. “Is this way we’re living the only one available to us?” Cesar memorably asks at one point. I would like to think so, but I’m far from sure about it.