No one is quite sure who originated the saying “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture,” though it has been repeated by Martin Mull, Frank Zappa, Steve Martin, Elvis Costello and many others. This has got to be the dumbest epigram ever. First off, it necessarily assumes that music writers are somehow trying to duplicate the ineffable ability of music to enrich our lives. Moreover, it is a prime example of someone willing to miss the point in the quest to make themselves look smarter than others. Considering that the saying is often used by musicians, it may just be they don’t like getting reviewed.

“Critics hate Van Halen and love Elvis Costello because most critics look like Elvis Costello”

-David Lee Roth, circa 1981

But with its limitless supply of colorful characters and tortured geniuses, artistic triumphs and cringe-worthy flops, jet-setting successes and undeserved obscurities, the music world is an endless repository of subject matter that also reflects on history, sociology, race, class, fashion and many other topics. Many authors have written very well about music, thank you very much.

Here is the first half-dozen, mostly taken from my trusty film-and-music bookcase at arm’s length to my desk. Part two will have six more and should arrive in time for any last-minute gift ideas for the music nut in your life. Of course, you can do that by asking at your local independent bookstore or by ordering from that great online retail place that begins with A. That of course would be Alibris.com, where all these titles are available.

“Fire and Rain” by David Browne (2011)

Author and Rolling Stone contributing editor David Browne finds the “Lost Story of 1970” by formulating a narrative that explains the end of the momentous Sixties through four iconic rock artists, the albums they released to usher in the Seventies and their personal stories at that time, extending it into the society at large. The end of the Beatles is explored through the bittersweet ”Let it Be” and the fitful start of four solo careers amid lawsuits and a retreat from the crushing weight of superstardom. Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge over Troubled Water” is seen as hymn-like response to social upheaval, “a much-needed respite from one piece of bad news after another.” Similarly, the mellow introspection of James Taylor and the popularity of his breakthrough “Sweet Baby James” is viewed as a reflexive response to revolutionary rancor. The chaotic interpersonal dynamics of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young provides Browne with plenty of choice material for a dissection of the drug-clouded judgments and hedonism of the day. Their “Déjà vu” album released in March featured themes of domesticity that quickly gave way to embittered protest of the “Ohio” single in the wake of that May’s Kent State killings (in one of the book’s many intriguing anecdotes, we find that two future members of Devo were attending school there at the time). This kind of musicology mixed with social history can be a tricky tightrope but Browne stays on the wire with a relevant voice that never gets ponderous.

“Rock Off: 50 Tracks that Tell the Story of the Rolling Stones” by Bill Janovitz (2013)

Writer and Buffalo Tom frontman Bill Janovitz, who also penned a book on “Exile on Main St.” for the “33 1/3” series, gets to expand on his appreciation and encyclopedic knowledge of the Stones with this intriguing concept. He explores the half-century career of rock’s defining bad-boy band by devoting one succinct chapter each to 50 different songs and how it relates to both their musical evolution and their life and times. This gives the oft-told tale of Jagger, Richards and Co. a fresh spin. The chronological spin is impressive, taking in both the Mt. Olympus material like “Gimme Shelter” and “Jumping Jack Flash” and some lesser-known gems like Aftermath’s “I am Waiting” and Bridges to Babylon “Saint of Me.”

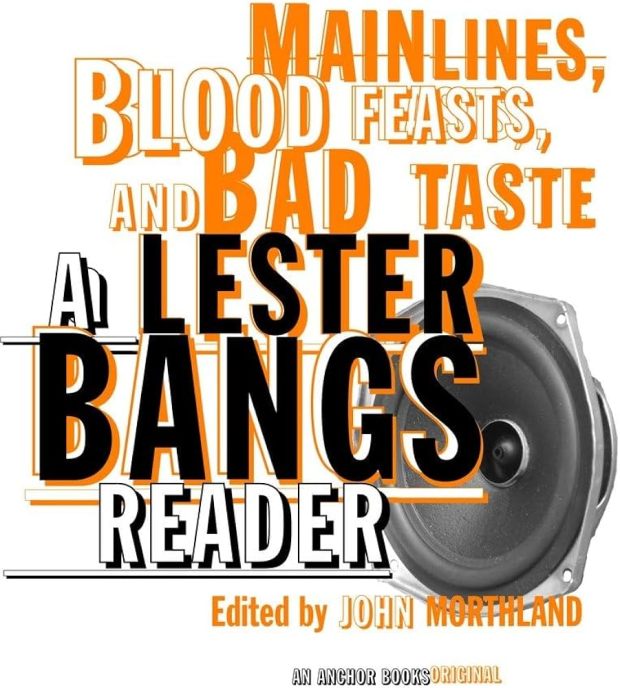

CREEM: America’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll Magazine

Edited by Robert Matheu and Brian J. Bowe (2007)

It was a classic “Merry-Xmas-To-Me” moment when this Creem anthology/coffee-table book turned up at my local late-lamented Borders store several Decembers ago. Ex-Creem photographer Robert Matheu and Brian Bowe, who helped develop the now-moribund Creem online site, compiled articles, interviews, photos, cover art and other quirky features of one of the most celebrated and irreverent music magazines ever published. From its gritty beginnings as a local counterculture rag in Detroit, through its 1970s heyday and on to its demise in 1988, Creem was a genre unto itself: “stripped down, no pretension but plenty of attitude, an urban lyricism and a wicked sense of humor” as says Paul Trynka in the foreword. Much emphasis is placed on the influential groups that Creem championed in the early days—there are multiple entries on the Stooges and MC5 and a prescient Ben Edmonds piece on the New York Dolls from summer ’73: “the main reason the Dolls have been so misunderstood is that they don’t play to any existing audience; it’s an audience that has yet to reveal itself.” Creem was long known as the magazine that gave its writers so much creative latitude that they often became stars in their own right and you’ll find them all here: Lester Bangs of course, as well as Dave DiMartino, Richard Riegel, Billy Altman, Lisa Robinson and the late Rick Johnson, who is represented in a couple of brief pieces, including a recap of his notorious feud with the Runaways. It would have been nice to see more than just a few entries from the famously feisty record-reviews section, where you were implored to buy albums from the Ramones and Sex Pistols while the complacent superstars of the day were pilloried on a set schedule (their take on Queen’s Live Killers? “Makes you feel someone is peeing on your grave.”) Considering that the Creem brand name, which various parties have been trying to revive for years, has been tied up in legal disputes, it’s amazing that a book like this ever got out, so if interested scoop one up while you can.

“In the City: A Celebration of London Music” by Paul Du Noyer (2010)

Paul Du Noyer is founding editor of the excellent rock-legacy magazine Mojo and although a native of Liverpool, proves himself as good or better than a native Londoner with this exemplary book about the music from and about the U.K.’s capital city. Comprehensive in content but sprightly in tone, Du Noyer’s 280-page history ranges from the broadside balladeers and singing street merchants of Medieval times all the way through to Lilly Allen. Befitting his background, the author does concentrate on the rock icons associated with the city such as the Kinks, the Who, Small Faces, Ian Dury, Elvis Costello, Blur, the Clash, Paul Weller (and other usual suspects) who are profiled as to how the city influenced their music and vice versa. But popular culture was not invented in 1964 and Du Noyer deftly ties it all in with antecedents like Noel Coward, Gilbert and Sullivan and music-hall star Marie Lloyd. “Popular songs have been the perfect expression of London’s character,” he writes on the very first page and finishes the thought a well-chosen appendix list of 140 London-related songs.

“Sonic Cool: The Life and Death of Rock ‘n’ Roll” (2002)

Iconoclastic rock scribe Joe S. Harrington wrote for a wide variety of publications (ranging from New York Press to Wired to High Times) before putting down his impassioned and schismatic views in this weighty tome that delineates the “massive cultural movement” called rock ‘n’ roll that is seen to be collapsing under its own weight at the turn of the century. But what a ride it was and Harrington includes most every significant event and sub-genre as well, with trenchant but entertaining analysis coloring chapters like “Elvis Gotta Gun”, “Kill the Business”, “The Revolution” and “Days of Malaise.” This is compulsive page-turning stuff for zealous rock fans already used to the literary stylings of Lester Bangs and Nick Tosches. The fact that the last chapter is called “Post-Everything” will let you know where this is going and though rock ‘n’ roll is not now what it was once, Harrington leaves us pondering the worth of “88 billion pieces of mass-produced plastic” still out in the world even after the controlling forces of big business has seemingly squashed the medium’s original (and occasionally re-occurring) rebellious instincts.

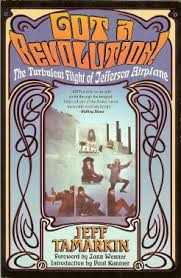

“Got a Revolution! The Turbulent Flight of Jefferson Airplane” by Jeff Tamarkin (2003)

When a famous band has a long history together, it can be ripe material for both a look into the evolving life and times of their days together as well as pump-priming for what are likely to be gossipy interpersonal issues. Well, the Jefferson Airplane story has plenty to offer on both angles and Tamarkin’s enlightening band biography is wonderfully adept at both. It traces the story of San Francisco’s signature acid-rock group through its small-venue early days before the Summer of Love, to its heady heyday as romantic and revolutionary figureheads of the late 60s and its eventual metamorphosis into the more consumer-friendly Jefferson Starship in the 70s and beyond. Suffice to say there are lots of literal highs and lows along the way and Tamarkin also traces some interesting storylines through the book’s arc, like how the band’s lawsuit against its original manager (with whom they signed a contract when they were young and idealistic) carried on into the 1990s as a famous test case. As far as the dirt-dishing, the author can leave a lot of that up to the participants as Grace Slick, Paul Kanter, Marty Balin and most of the rest were interviewed and their colorful comments are sprinkled oral-history style throughout.

Hopefully by summer 2015 I’ll be “dancing about architecture” myself, when my next book “Rock Docs: A Fifty-Year Cinematic Journey” is due to be released.