The 1975 science-fiction drama “Rollerball” was a bit of an odd duck of a film: come for the bloodsport, stay for the philosophy. Some weren’t buying. Though a success at the time, this movie has always split viewers and critics. While not sensationalistic enough for certain action fans, it was sometimes seen as too plodding in its thematic thrust by the smarties.

But for someone like me, who enjoys thoughtful sci-fi but also grew up watching Roller Derby on late night TV, “Rollerball” hits just right. Its stature has grown over time and is well worth a look now, esp. as the near future it predicted (the film is set in 2018) has come to pass by several years. (Please note that I’m recommending the James Caan-starring original and not the inconsequential 2002 remake, which currently has a 14% rating om Metacritic).

Directed by Norman Jewison, with a script by William Harrison based on his own short story, Caan stars as the foremost superstar of a global sport that combines elements of the old banked-track skating derbies with motorcross and barely-controlled mayhem. Jonathan E. by name, this seemingly indestructible team leader excels like no other at jamming the heavy silver ball into the goal without getting maimed for life (it’s not unusual for there to be fatalities during these “games”).

The setting is what I would call a “model dystopia,” where war has been eliminated and all material wants met in a world is run by a cabal of supposedly benevolent corporations. Rollerball is the one unifying element for regular folk to have a visceral outlet for the violence which has supposedly been eliminated otherwise. The game is tightly controlled by the corporations, who are starting to think that Jonathan E. is transcending this concept of social control.

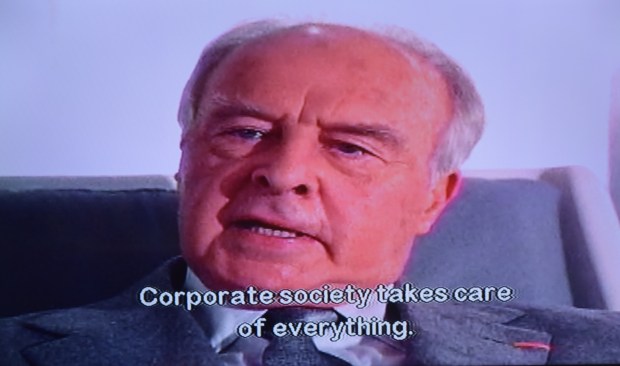

The plot is simple: the corporation wants Jonathan to retire, Jonathan does not want to and attempts to use what leverage he has to resist. No offense to James Caan, who was at the height of his movie-star power and acquits himself well, but the real star of the show is John Houseman as head of Houston’s Energy Corp. and who runs the locally based team.

Houseman, who came up in the theater working with Orson Welles, enjoyed a late-career resurgence as a character actor, winning an Oscar for his imperious Harvard law professor in 1973’s “The Paper Chase.” He is similarly authoritative here, making perfect use of his haughty mid-Atlantic accent which he later employed in memorable TV ads.

His Mr. Bartholemew is a tough nut to crack but Jonathan E. pushes back, wanting to know how their decisions are made, and even to get to the bottom of the mysterious “corporate wars” that brought forth the “material dream world” that he apparently doesn’t appreciate enough, especially in view of the luxury lifestyle he is guaranteed even after retiring.

Aside from the fact that he loves the game and is loyal to his teammates, it is sometimes hard to understand Jonathan’s motivational end game. If he were to beat the global conglomerate, what would he do: bring back war and poverty? I’m kidding, but this does bring up a core problem with the model dystopia brand of futuristic fiction. I recently re-read Adolus Huxley’s classic “Brave New World,” which “Rollerball” resembles in its false-utopia of Pavlovian conditioning helped along by easy access to pleasure drugs and the state-sanctioned rotation of sex partners.

Yes, we have no books: James Caan as Jonathan and (left) John Beck as teammate “Moon Pie”

Bernard Marx, Huxley’s morose protagonist, does rebel against the mindless contentment of his world, chafing against the notion that “Everybody’s Happy Nowadays,” a phrase that inspired the great punk-rock single by the Buzzcocks. Bernard’s attempts to buck the system predictably leads to disaster and although Jonathan’s fate after the film’s climatic and grisly rollerball championship is left ambiguous one is left pondering: when we get the real-world dystopia we have coming to us, it probably won’t be with this government guaranteed sexual fulfillment and free Ecstasy. Just saying.

But although the expository scenes of this film may slow it down at times, Norman Jewison’s artful direction makes it a great watch. Jewison (whose credits include In the Heat of the Night, Fiddler on the Roof, Moonstruck and the original Thomas Crown Affair), was one of those versatile, populist filmmakers of his era—Sydney Pollack and Walter Hill are two others—who did consistently fine work without ever being considered an auteur.

Perhaps to counter audience desensitization, the corporations keep upping the ante, until the final match is played with “No penalties, no substitutions, and no time limits,” essentially setting up a “Hunger Games” type scenario.

Despite that his work here has a certain Kubrickian vibe. “Rollerball” has shades of “Clockwork Orange” in its ultra-violence and “Eyes Wide Shut” in its upper-class decadence—and even a bit of “2001” in the forbidding hi-tech architecture of the corporate state (provided by the then-new BMW Headquarters in Munich). It’s here that master thespian Ralph Richardson gives a humorous late-career performance as the head “librarian” whose actual job is to tend to the overtaxed super-computer called Zero. In a movie that needed a little comic relief, the befuddled caretaker explains to Jonathan that Zero (who earlier that day “lost the 13th Century”) is so smart that “his borders touch all knowledge.” But the librarian also admits that Zero, who “considers everything,” seems to not know anything at all.

This is perhaps the film’s most prophetic moment, pointing to our own superconnected/disconnected present world. It sends Jonathan E. back to the rollerball arena safe in the knowledge that: Yes, We Have No Utopias.