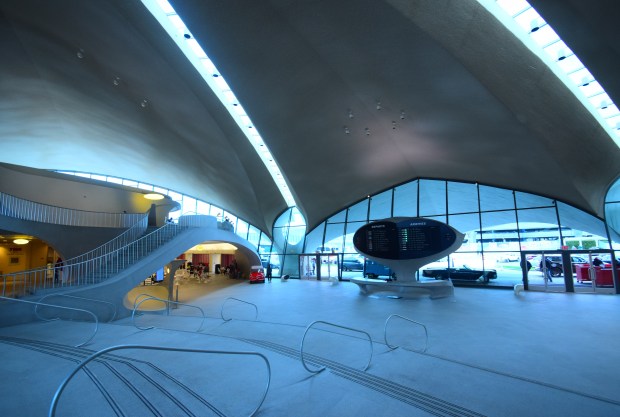

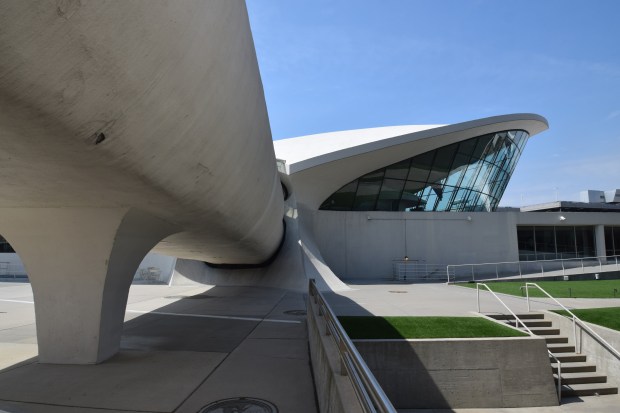

An instant induction into the “Placeology” Hall of Fame goes to the TWA Hotel at the JFK Airport in Queens, New York City. Eero Saarinen’s Jet Age/Space Age masterpiece, opened in 1962, now serves as a gigantic retro-futurist lobby for a hip but friendly destination hotel. The actual guest rooms are in two curved buildings that overlook the great sculptural form of Saarinen’s creation, made to resemble a bird taking flight. You reach the rooms by walking up the terminal’s two iconic red-carpeted tubeways, which may make you feel like you’re living inside the space station scenes in Stanley Kubrick’s “2001.”

Those ramps once led directly to the jet doors, previously passengers had to head out on the tarmac and climb the roll-up stairs in all sorts of weather. They’re indicative of the efforts of Trans World Airlines, with Howard Hughes still as principal owner, to popularize and glamourize the growing airline industry. The sunken lounges, curvaceous stairways, giant viewing windows, in fact everything down to the chic uniforms and pillbox hats worn by the stewardesses, led to a total implied package of adventure and elegance. (Compare to today!).

So you will see walls lined with photos of the Beatles, Muhammad Ali, Presidents Kennedy and Truman and movie stars ranging from Marilyn Monroe to Paul Newman. Of course, you don’t have to be a big shot to stay at today’s TWA Hotel. It’s a bit pricey but not exorbitant when compared to far less attractive places. Since airports are not standard vacation destinations, the people who are staying at the TWA are usually there because they appreciate it (an exception may be if your flight at the adjacent Jet Blue terminal was cancelled until the next day).

There is certainly lots to appreciate. The hotel is fun and distinctly non-snobby, as amenable to young families as it is to couples on a romantic getaway. The latter can enjoy a drink in the sunken lounger under one of the terminal’s two giant elliptical Arrivals & Departures boards, while the former can entertain themselves by checking out the Twister game room, the many vintage automobiles and the free photo booth. Aside from the soft clattering of electro-mechanical A&D boards, the main sound you’ll hear is the continuous sound of Sixties pop music over the PA, just loud enough to be a nostalgic soundtrack of your stay. Along with the sounds of the British Invasion, Motown, surf, early rock ‘n’ roll and the occasional Frank Sinatra croon, you get a couple of tunes from the girl-group pride of Queens, the Shangri-Las.

A big attraction for many is a restored propeller-driven Lockheed Constellation, an airliner that was produced between 1943-58. Its bold profile dominates the view outside the terminal’s huge oval rear window. Affectionately known as “Connie,” any guest is free to go outside and walk up the steps, where the interior is now an informal lounge (expect a crowd). But there will much less of a crowd in the terminal’s “hidden” nooks and exhibit rooms, where the hotel’s playful quality really hits a peak. There’s the “Pope Room,” a tiny vestibule where Paul VI decompressed in October of 1965 after becoming the first pontiff to set foot in the U.S. At the end of one of the tubeways you can visit (and hang out in) a recreated Sixties living room, a TWA executive office, and a simulation of Saarinen’s studio.

After settling into the fantastical realm of Eero’s creation, you may notice something which is the most gratifying feature of this whole experience: that to whatever extent possible, the developers of the TWA Hotel left this architectural gem as is. The building had been essentially vacant since the terminal was last used in 2001 until it opened as a hotel about five years back. But there was no Disneyfication in the rehab: the carpets, seat cushions, tiling and concrete sheathing are all original and a bit timeworn, even a little tatty in places.

It cost a little more for a room with a “historic view,” but it is worth it.

That’s a good thing. We are invited into (for the price of a room) a real and vital piece of design history, not a replica. As you walk towards the hotel, you will enter this rarefied air with the help of outdoor speakers playing the 5th Dimension’s bouyant hit version of Jimmy Webb’s “Up—Up and Away” which was adapted into a memorable TWA television commercial. Along the way you will see translucent posters, partially blocking views of the construction of a new international terminal, that feature press testimonials of New York’s “sexiest” hotel. The one that stuck with me was from the Wall Street Journal: “They don’t build them like this anymore, and they never will again.” Truth.

Photos and text by Rick Ouellette