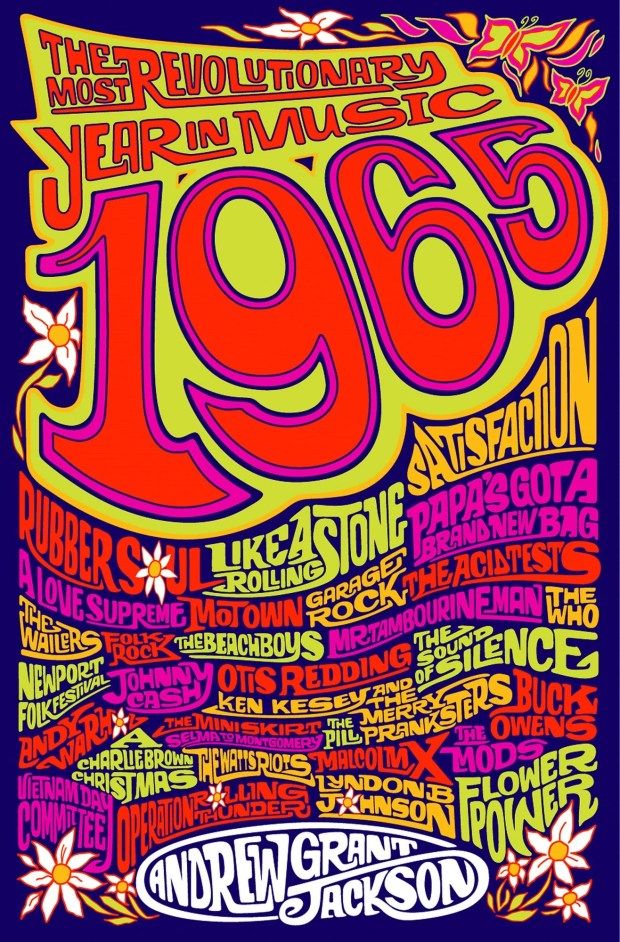

It was 60 years ago that the music world was turned on its head, smack dab in the middle of that terrific and turbulent decade. While there is room for debate as to what was “the most revolutionary year in music,” rock scribe Andrew Grant Jackson makes a great case for ’65. Consider masterwork albums ranging from the Beatles’ Rubber Soul to John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. How about era-defining singles like “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” “Eve of Destruction,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag,” “My Generation” and “The Sound of Silence?” The year also saw the rise of garage rock and psychedelia. And it all happened against the backdrop of tumultuous events like the Watts Riots and the first large-scale protests over the Vietnam War.

What makes this book so compulsively readable is Jackson’s knack for conflating musical events with related social themes of the age. One of the best examples is the advent of the Pill and the concurrent dawning of the “Free Love” era and the shattering of the age-old “Madonna/whore” complex, at least among the younger generation. (Women with the upper hand started making appearances in Beatle songs like “Day Tripper” and “Ticket to Ride”). Models such as Edie Sedgwick and Twiggy were “waifish and full of wonder” and made words like “tramp” seem suddenly outdated. Jackson writes: “An act (casual sex among unmarried people) that had always been shameful now acquired a butterfly-winged lightness.”

Edie Sedgwick and Twiggy

But it was still largely a man’s world and Bob Dylan’s “Like A Rolling Stone,” which has been praised to high heaven for six decades, is a rather harsh put-down of a poor little rich girl—supposedly inspired by Bob’s brief affair with the vulnerable Sedgwick. Brilliantly composed for sure, but I prefer the more spiritual “Mr. Tambourine Man” as my 1965 Dylan touchstone. The Byrds’ #1 hit version in June was the early high-water mark of the folk-rock movement.

Jackson points out that, in a year which saw the savage attacks on civil rights marchers in Selma and elsewhere, it was in the music world that pointed the way to positions of peace, solidarity and understanding. The Temptations’ “My Girl” was #1 pop hit the same week that ABC interrupted the Sunday Night Movie to show Alabama state troopers brutal attack on non-violent black demonstrators.

When the Beatles invented the big stadium rock concert at New York’s Shea Stadium in August, the opening acts were Motown singer Brenda Holloway, jazz/soul saxophonist King Curtis and the Mexican-American band Cannibal and the Headhunters. It was the type of diversity that didn’t have to announce itself. Things were bubbling up all over: in Jamacia the new reggae band Bob Marley and the Wailers released no less than 17 singles that year, including an early version of “One Love.”

Another sign of increasing cultural cross-pollination was the dawning influence of Indian culture. The first salvo was the bewitching drone ambience of the Kink’s “See My Friends.”

Then there was the fateful moment when George Harrison met up with a sitar on the set of “Help!,” the Beatles’ second feature film that was shot in early ’65. By year’s end George was playing one himself on “Norwegian Wood.” More importantly, the group was gifted a copy of Swami Vishnudevananda’s “The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga,” The more serene, inward-looking type of wisdom offered by Hindu philosophy would become hugely influential in the years to come, offering an alternative to the kind of might-is-right that brought the U.S. into the Vietnam quagmire.

While the year 1965 may not ever be considered as relevant as Summer-of-Love 1967 or Woodstock 1969, Jackson has made a very compelling case that the groundwork for all that came later is in the Big Bang year of ’65 and this brilliant page-turner will have you convinced. —Rick Ouellette