The live album holds a curious place in many discographies of rock bands and solo artists. It can be many things: a peak-career highlight for some (The Who’s Live at Leeds, the Stones’ Get Yer Ya-Yas Out, James Brown’s live-at-the-Apollo recording) and a career maker for others (Frampton Comes Alive). Many others are seen as placeholders between studio albums or as a de facto souvenir for fans who have seen their favorites in concert.

Sometimes though, an official live release can end up being a millstone in the canon of even the best musical artists, scoffed at by both critics and fans alike. It could be a case of shoddy production, sloppy performance, a group in career downturn or even an excess of success. Creem magazine was once so put off by the rank triumphalism Quenn’s Live Killers they compared it to the sound of “someone peeing on your grave.”

Over time I have gathered up a list these bad-rep concert documents and re-visited them, wondering if they really deserved all those one-star reviews. In some cases, time has been kinder, initial victims of a hot-take hostility in a tougher age of music criticism. Others are still big-time stinkers.

Who’s Last—The Who (1984)

I’ve always wondered about this one. Dismissed and derided at the time, Who’s Last was a document of the band’s at-the-time Farewell tour back in 1982. I mean it couldn’t be as bad as all that, right? Yes and no. On one hand it is the Who and there are gobs of great tunes that are played well enough. But on the other hand, don’t expect anything transformative. The galvanizing versions of “Magic Bus” and “My Generation” on the celebrated Live at Leeds put the ones here to shame, not to mention how poorly this “See Me, Feel Me/Listening to You” stacks up to victorious version on the Woodstock soundtrack. True, people thought it was a swan song back then and a release was justified (though it only hit #81 in America) but after Pete and the boys resumed touring in 1989 it seemed irrelevant, esp. after the sublime Leeds was expanded from 6 to 14 tracks in the CD era. Grade: C-

Take No Prisoners—Lou Reed (1978)

“What do I look like, Henny Youngman up here?” Yeah, kinda. This smart-ass double album was reportedly Lou’s answer to those who said he never talked on stage. True to Reed’s incorrigible nature he goes too far in the other direction, ad-libbing over opener “Sweet Jane” until the song is just an afterthought. True, he does get out a few good lines (“Give me an issue, I’ll give you a tissue”) and a sick burn on Patti Smith (“Fuck Radio Ethiopia, this is Radio Brooklyn!”) but it sets the tone for what is really a punk novelty record.

The crowd at the Bottom Line nightclub in NYC seem to be there as much for the cult of personality as for the music, and “Walk on the Wild Side” becomes a rambling 16-minute monologue a la Lenny Bruce. When Lou does manage to get thru a whole song without ragging on rock critics or his old Factory friends the results can be pretty good, as on “Coney Island Baby” and “Satellite of Love,” but they add up to a relatively small fraction of the album’s long 98-minute run time. Grade: C

Coast to Coast: Overture and Beginners—Rod Stewart/Faces (1974)

The Faces were on borrowed time when this concert record came out, maybe accounting for the poor press it got. Some saw it as a quick cash-out before Rod Stewart finally split to commit full-time to his burgeoning solo career. Key contributor Ronnie Lane had already left, replaced by Japanese bassist Tetsu Yamauchi. Coast to Coast is an enjoyable (if slapdash) mix of Rod solo numbers, a couple of Faces songs and clutch of covers. Most successful is a top-shelf take on the Motown lament “I Wish it Would Rain,” featuring an impassioned vocal by Rod and a great blues guitar solo from Ronnie Wood. Grade: B-

On the Road—Traffic (1973)

Traffic were another stalwart British group who were heading down the home stretch when this leisurely live double hit the shops. They released one more studio album before disbanding the following year. This was the end of their expanded-lineup era, with the core trio of Steve Winwood, Jim Capaldi and Chris Wood were joined by percussionist Rebop and three Muscle Shoals session men. This period was marked by a certain languid jam-band sound and most of the material here was drawn from the previous two studio sets, Low Spark of the High-Heeled Boys and Shoot Out at Fantasy Factory. The only nod to the “old” Traffic was a 21-minute medley of “Glad/Freedom Rider.” The band may have set themselves up for rock-mag ridicule by including the recent “(Sometimes I Feel So) Uninspired.” But that one turns out to be a highlight, with some electrifying lead guitar from Winwood, so go figure. Grade: B-

David Live—David Bowie (1974)

This is a textbook case of a concert album being recorded at precisely the wrong time. Bowie’s ’74 show started off as the “Diamond Dogs” tour and ended as the start of his “plastic soul” era. (His next album would be Young Americans). The album is unfocused and lacking in true energy, his vocals careless and strained. Hard drugs were an issue. It tends to sound better if you don’t know the studio version and have nothing to compare it against (I rather like his version of the Ohio Players “Here Today, Gone Tomorrow”). But the only one of his many famous songs here that maybe outdoes the original is a strong version of “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide,” that closes this misbegotten release. Grade: D+

T.V. Eye Live—Iggy Pop (1977)

Speaking of Mr. Bowie, the year 1977 brought him renewed recognition not only for two of his classic Berlin-era albums (Heroes and Low) but also reviving the career of a certain James Osterberg, who was at loose ends after the dissolution of his proto-punk band the Stooges. Iggy Pop, as he was better known, joined Bowie at his digs hard by the Berlin Wall, both trying to kick long-standing drug habits and get new inspiration in their bleak Cold War surroundings.

Iggy also released two great albums in ’77 (The Idiot and Lust for Life), both produced and largely co-written by his pal Dave. This single live album also got a release but was panned across the board (one meager star at AllMusic) but nowadays it’s hard to see why. It’s a pretty strong set, some of it from an American tour where Bowie supported him on keyboards and backing vocals. The sound quality is not so hot, probably because RCA gave him a $90,000 advance to produce the album (he owed them one more LP) but then spent five grand on it and pocketed the rest. That alone bumps it up half a grade. B+

Bob Dylan at Budokan—Bob Dylan (I think) 1978

Perhaps we will never know just what compelled Zimmy to release this album of his revolutionary repertoire performed as a vacuous Vegas lounge act (and presented as such). On the heels of his divorce and the epic flop that was his “Renaldo and Clara” movie, maybe he thought he could release a quicky double live album and recoup his losses before anyone noticed, it did hit #13 in America.

It did have a few critical defenders and of course if you go by the YouTube fanboys, Budokan ranks right up there with the Sistine Chapel at the apex of Western Civilization. But unless it’s enjoyed as a perverse form of performance art, I don’t know how anyone can like the Wayne Newton arrangements, the cloying back-up singers, the overwrought saxophone and Dylan singing his visionary back catalogue as if it were the collected works of Tony Orlando and Dawn. Just take this encore version of “The Times They are A-Changing” (please) and listen to the fake sincerity of the spoken intro and then Dylan actually telling the crowd “We’re here for four more nights” as if he really were at a casino cocktail lounge and not one of the world’s most revered concert halls. Wow. Grade: D

Still Life—The Rolling Stones (1982)

The era of the true mega concert tour, complete with corporate sponsorship, was under way in the early 80s and naturally the Stones were on the leading edge. That means fans packed in like 80,000 sardines at a place like Arizona’s Sun Devil Stadium and the band trying to fill it with sound and vision no matter how impersonal the setting. (You can see some of that scene in the Hal Ashby-directed tour film, “Let’s Spend the Night Together”). The stage is so big that Mick Jagger and Charlie Watts seem to be in different zip codes). This dynamic comes thru in the unfortunately- titled Still Life.

Like Who’s Last, there are lots of great songs here and the notes are all in the right place (mostly). Yet, it comes down to a business model that just doesn’t work—for me, anyway. I’ve never been to a football stadium concert, and this shows me why. Sure, it’s quite possible to have a good time at this kind of show (many have) but to me the possibility of a good aesthetic return on your monetary investment seems low. I can’t see the band and they can’t reach me; that dubious dynamic carries over to the album. Like David Live, this album sounds OK when you don’t have any previous recording to compare it to, so I chose their new cover of Smokey Robinson’s “Going to a Go-Go” as the best of the lot. Grade: C

Live ‘n’ Kicking—West, Bruce and Laing (1974)

Twin Peaks—Mountain (1974)

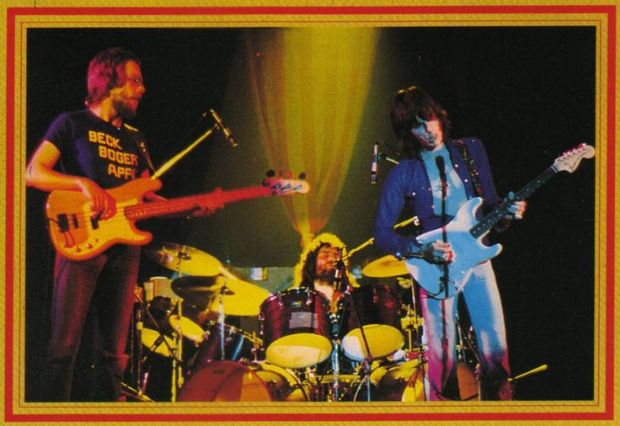

When you apply the contemporary phrase “Go big or go home” to the classic rock era, it’s hard not to think of Leslie West. He was a “mountain” of a man (his girth inspired the band’s name), his bellowing vocals and scorched-earth guitar solos known far and wide since the band made a big splash at Woodstock. By 1972, Mountain were on hiatus and West and Mountain drummer Corky Laing joined ex-Cream bassist/singer Jack Bruce to form a blooze-rock supergroup that released two studio albums and this single live set, released just after announcing their break-up in early ’74.

As a group, Mountain, as heavy as they were, also had a melodic sign, seen in deft compositions like “For Yasgur’s Farm” and “Nantucket Sleighride.” WBL cast away most of that. To start off Live ‘n’ Kicking, they turn the Stones’ refined and brooding ballad “Play With Fire” into a 13-minute marauding metal warhorse, complete with drum solo. The “96-decibel freaks” in the audience eat it up. Jack Bruce, replacing the more refined Felix Pappalardi as West’s frontline partner, was rougher-edged. He fills the space between songs with arena-rock bravado and his bass is turned up to overload levels nearly as loud as West’s guitar, if that’s even possible. True, there is some nimble trip interplay on the WBL original “The Doctor” but things go happily off the rails with closer “Powerhouse Sod” which turns into a Bruce showcase, because everyone knows the best way to end a 70s live album is with a bass solo!

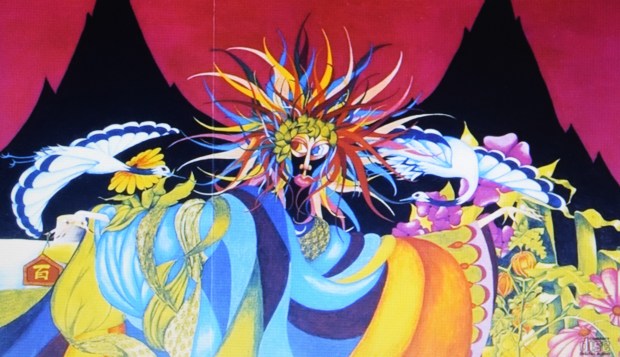

Around the same time that West, Bruce and Laing were dissolving due to internal dissension and hard-drug abuse, West was and Pappalardi were re-uniting with a new lineup. Corky Laing, for whom the drug issues were hitting esp. hard, was replaced this time by Alan Schwartzberg. Original keyboardist Steve Knight was subbed off in favor of Bob Mann, who also doubled on second guitar for added sonic impact. My roommate at the time called the Japan-recorded Twin Peaks “the album with the biggest tits in the world” (riffing on Monty Python) and it did seem like the band was out to prove scale new heights of heavyosity.

Twin Peaks, with its confident air attractive artwork (see banner image at top of this post) did fare a little better in the critical arena than Live ‘n’ Kicking, which got an E+ (?) in the Village Voice. However, many scribes headed for the exits at the prospect of a 32-minute “Nantucket Sleighride.” Of course, fans, in this age of bong hits and good stereo systems, loved every long minute of it and didn’t mind having to get up and flip the record halfway thru. The glorious noise continues right through to side four, as the band run over the “Mississippi Queen” with a Mack truck and play “Roll Over Beethoven” at such volume that it would have made ol’ Ludwig van deaf all over again. Best of all is West’s signature “Guitar Solo,” where he gets free reign to indulge himself for five uninterrupted minutes, to the point where he injects a bit of “Jingle Bells” even though it’s August in Osaka. The Seventies, they were a thing, man.

Grades: Live ‘n’ Kicking: B-, Twin Peaks: A (fight me).

And speaking of “Jingle Bells,” Happy Holidays, everyone!