It’s been about ten months since part two of this series. In the long interval before this concluding entry, a long unfolding social problem has received more and more media coverage. A front-page headline last September in the Wall Street Journal summed it up rather neatly; “The New Asylums: Jails Swell with Mentally Ill.” The story tracked a pattern from the mass closings of outsized state hospitals in the 70s and 80s to the subsequent rise in the homeless population as many patients went from overcrowded (and sometimes abusive) facilities to no care at all. The ideal of a community-based middle way never really took hold and while advances in pharmaceuticals to treat psychological ailments have helped those with less severe cases, many others fell between the cracks during that process and in the years since. The situation just seems to get worse. Today, as I was getting set to put up this post, a major page-one report in the New York Times detailed the severe injuries suffered by 129 inmates at the hands of correctional staff at the huge Riker’s Island jail between the Bronx and Queens. A full 77 per cent of those inmates had been diagnosed with mental illness.

Obviously, this is a difficult problem and a tough one to get right. No one wants to go back to the warehousing asylums of old, where people could be committed for an indefinite stay on some flimsy pretense, like vagrancy or for being a troubled child that a parent could no longer deal with. But this downward spiral of insufficient mental health resources, underemployment, homelessness, drug abuse and petty crime invariably leading to incarceration is disheartening if not scandalous. Where’s the proper middle ground?

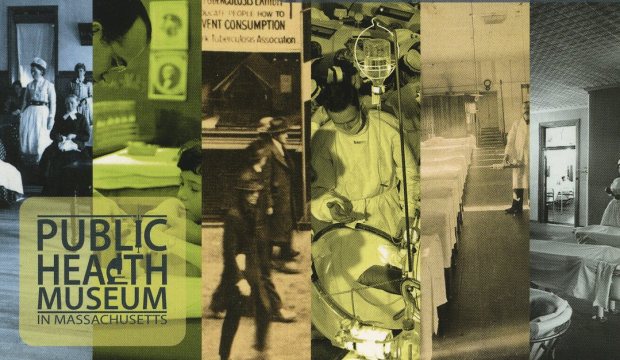

I recently made a couple of visits to historic Tewksbury Hospital, the prominent Old Administration Building of which, seen at the top, was built in 1894 in bewitching Queen Anne style. It’s been continuously in operation since 40 years before that, first as an almshouse (Anne Sullivan lived there before becoming Helen Keller’s tutor and friend) and then used for the treatment and containment of contagious diseases. Although it was operated by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and mental health care did figure in the mix throughout its history, it was never a state hospital in the way we would come to think of it—the overcrowded and malignant institutions on large campuses that have in their closed state become havens for urban explorers. But when one of the more infamous such places (Danvers State Hospital, as discussed in previous installments of this series) closed in 1992, the Mass. Dept. of Mental Health moved from there to Tewksbury and—along with the Dept. of Public Health—established the Public Health Museum there two years later.

The museum is tucked into one section of the Old Administration Building’s first level. This ground floor is a beautifully restored wood-paneled interior that the unfortunate people being admitted here never got to see, if a preserved sign near the front entrance is any indication.

Much of the exhibit space is given over to showing the evolving history of methods for treatment of physical maladies, and you can see antique wheelchairs and an iron lung for real. But another room shows a similar backstory for mental health treatment. This will be the chilling highlight for many visitors. The curators, to their credit, do not shy away from showing patient treatments that nowadays would be considered barbaric or shocking. Otherwise, they wouldn’t have a mannequin strapped down to a bed to show any and all comers exactly what insulin-induced coma therapy looked like back in the day:

Another interesting factoid I learned there: Danvers State once had a baseball team.

You’re free to stroll the grounds at Tewksbury, which has an old formal gateway and other buildings of architectural interest. But it’s still an everyday working hospital. People ‘round my neck of the woods who want to get a feel for one of the classic creepy institutions can head south of Boston, where the isolated ghost town-sized Medfield State Hospital has been opened for people who want to have a walkabout. This is one of the few places I know that have done this, maybe as a co-opting measure for the hundreds of people who have seen these places as targets for infiltration. Of course, rules state that going inside the boarded buildings is strictly verboten. Still, it’s a great way for us urban-explorer dabblers to daytrip without worrying about getting nicked for trespassing. Now made safe for family excursions, I took along Ryan as my urban-explorer-in-training and lens-changing assistant.

Although drastic methods like insulin or shock therapy may have been seen as necessary to control the worse-off patients, the power that comes with such authority still tempts abuse as we found out recently here in Massachusetts. Bridgewater State Hospital is site of Frederick’s Wiseman’s muckraking and groundbreaking 1967 documentary “Titicut Follies” (see Part 2 for more). It was reported in June that BSH was in danger of losing its national recognized hospital accreditation after it was found staff had significantly increased the use of isolation and strapping, even after the 2009 death of a patient during the application of restraints. Granted, Bridgewater is actually a medium-security prison that happens to house the most severely mentally-ill people in the state. But it also pointed out the thorny no-man’s land that exists between incarceration and the proper levels of mental health treatment. After a ban of “Titicut Follies” that lasted a quarter-century for “invading the privacy” of inmates (even though he had full clearances), Massachusetts courts finally allowed Wiseman to air his devastating expose of institutional abuse as long as he included a disclaimer at the end saying conditions have since approved at Bridgewater. The director’s one-sentence disclaimer, blankly using that very phrase, spoke volumes.

Walking off the grounds at Medfield State, we caught view of the above. Who wrote this? Driving away, thoughts bounced around on different angles. Was it a mocking ex-inmate, a droll site worker, an urban explorer? There are certain people who get creeped out at the thought of these sites of suffering being converted into semi-affluent residential communities (possible sales blurb: “Nowadays, you would have to be crazy NOT to live here”) and the sign seemed to reflect that. That didn’t seem to affect folks who streamed into the old Danvers State property, re-purposed by Avalon Communities.

“And over there is where they invented the full frontal lobotomy. Care for a swim?”

This spring I snuck onto the perimeter of the now-closed Fernald State School in Waltham, Mass. (see part 2), to visit a geographical feature that had always intrigued me but that I’ve never been able to classify. It began just off to the side of the Fernald Volunteer Center, a veritable Boo Radley house that despite its disrepair, always seemed vaguely occupied. During the time we lived on a street just across the way, I’d often turn my bike into a mowed section of field that dipped down below the level of Trapelo Road and continued for several hundred yards. I would pedal along a meandering path behind the also-closed daycare place, and through a wooded section that then opened up into a boulevard-wide lawn that undulated in sunny seclusion before returning to the gloomy main grounds, where once thousands of unfortunate (and usually quite young) patients lived. Until recently, even when there was only a couple of dozen patients left on the vast campus, someone dutifully mowed this obscure stretch of land on a regular basis. Thinking of the shaded sanatorium walks of old, I wondered if this had been a place where patients were brought to for a “country” walk. It would have been a brief respite—if it ever even happened—for a cruelly exploited class of luckless people who were otherwise liable to be the subjects of unconsented experiments: the children who were fed radioactive isotopes or autistic kids given doses of LSD for months on end. Soon this place will cover itself up, unseen and all but forgotten but leaving a lot of questions in the air about what’s left to do after all the hell holes are abandoned in place.

I had no idea you had undertaken such a project! I’m not sure I was following your blog back when “Part 2” was posted. Nevertheless, it’s a morbidly interesting one. I stumbled into a social policy class in college on mental institutions, policy, and the homeless, and it was sobering indeed. Have you ever read “Is There No Place on Earth for Me?” by Susan Sheehan? I still have trouble believing that it’s nonfiction. That’s not to say that it’s the best-written thing in the world (I only gave it 3/5 stars, apparently), but it’s certainly compelling.

Thanks for the suggestion, I will look it up. Sorry for the late reply, I was on vacation and off da grid, so to speak

Great Post!

Thanks, I was inspired by some of your posts to work more photos in. It really makes a difference.