The big duality of the 1960s was the great aesthetic leaps made in music, film and other artistic fields, countered by the social and political upheavals of the time. Of course, the former often fed off the latter but there was also just a lot of great escapist entertainment. Then came 1968, a year marked by escalation of the Vietnam War, assassinations, violent clashes between police and political demonstrators and the election of the divisive Richard Nixon to the U.S. presidency.

For rock musicians, recognized to be in the vanguard of the era’s youth movement, it was time to stand up and be counted. And so it was for the New York-based Rascals, who had recently dropped the “Young” from their band name. They had spent the previous few years as top-line hitmakers who combined infectious blue-eyed soul with progressive pop values. The AM radios of the day were often graced by their presence, from party anthems like “Good Lovin’” and “Mustang Sally” to sweet summery treats like “Groovin’” and “It’s a Beautiful Morning.”

NEW YORK CITY – JUNE 28: (L-R) Felix Cavaliere, Dino Danelli, Eddie Brigati and Gene Cornish of The Rascals attend Martin Luther King Jr. Benefit Concert on June 28, 1968 at Madison Square Garden in New York City. (Photo by Ron Galella, Ltd./WireImage) *** Local Caption *** Felix Cavaliere, Dino Danelli, Eddie Brigati;Gene Cornish

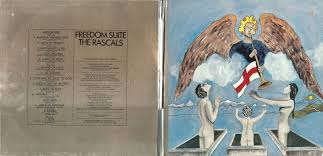

But the spring of 1968 was not the time of escapism. In the wake of the killings of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, the band (vocalist Eddie Brigati, keyboardist-singer Felix Cavaliere, guitarist Gene Cornish and drummer Dino Danelli) released “People Got to Be Free” a song that sounded both sobering and uplifting in its aspirational optimism. It became one of the hallmark songs of that era, staying at #1 for five weeks that summer and eventually selling some four million copies worldwide. Soon, the Rascals were in the studio for the follow-up album named Freedom Suite, released in March of ’69. It was a lushly packaged double-decker album that would pair up two sides of more conventional tunes with a second record of instrumental numbers.

It was a curious volume, perhaps an effort by the group to be taken more seriously as album artists at a time when rock’s horizons were broadening. Freedom Suite starts out strikingly with “America the Beautiful.” Not exactly the patriotic standard—though they do quote it and give credit to the original composers—but a reworked version that gives voice to the inequalities and injustices that have smeared that sunny vision. After a symphonic stating of the theme and Danelli’s drummer-boy snare work, the tune takes on a ragtime feel as Cavaliere sings of how a nation he loves has strayed, esp. noting the failings of the War on Poverty from an Establishment for whom “the dollar bill is as far as they can see.” This kind of social commentary is echoed on several other songs. Most notable is the remarkable “Look Around” whose uplifting melody (a Rascals specialty) is tempered by woke lyrics (“hate and fear got ten million votes this year”) and sound effects of sirens, gunfire and marching soldiers. But typically for Cavaliere and Brigati, who penned this and were the group’s primary writers, the emphasis is on working towards positive outcomes and the song ends with a burst of children’s laughter.

This positivity shines brightest on “People Got to Be Free,” included here towards the end of side two. “If there’s a man who is down and needs a helping hand/All it takes is you to understand and/To pull him through,” the song gently implores, while its memorable chorus promises a “lovely, lovely world” if only everyone could practice this golden rule. Interestingly, the song was only partly inspired by the MLK assassination that spring. Around the same time the group’s van broke down in rural Florida, leading them to be hassled for being no-good long-haired hippies, a la “Easy Rider”. And so it goes.

Elsewhere on Freedom Suite, the Rascals revert to old ways with Eddie Brigati cutting a rug and proclaiming “Any Dance’ll Do” and Felix going full soul-revue on “Baby I’m Blue.” Guitarist Gene Cornish also contributes two tunes and really shines on the nostalgic waltz-like number that recalls a time when “Love Was So Easy to Give.” The second disc is a whole other ball of wax. The guys did have bona fide jazz influences and experience in high-profile house bands, three of them having played with Joey Dee and the Starliters at the famous Peppermint Lounge in Times Square. But the stretching out here (two of the three cuts here clock in a way over ten minutes) could have used more focus. In fact, “Boom” was a 13-minute Danelli drum solo, without even the benefit of an opening and closing band theme. Dino was a legit jazzbo, having played with Lionel Hampton and Red Allen, and the playing is great but this is pretty indulgent even by late Sixties standards. The full band is present for the sidelong “Cute” which works better. There are fine solos by Cavaliere on organ and Cornish’s needling lead guitar, and a drum-and percussion workout (with Brigati on congas) that could have replaced “Boom” altogether.

This double album would prove a tough sell for casual fans, many of whom already owned the #1 single from several months before. Freedom Suite peaked at #17 (and at #40 on the R&B chart) but slipped away not long after and two additional singles from it cracked the Top 40 but not by much. The Rascals continued making high-quality music but without the commercial success they were used to. In 1971, after the departure of Brigati and Cornish, a new line-up put out another double LP (Peaceful World) that continued, with the help of greats like Ron Carter, Alice Coltrane and Pepper Adams, with the jazz explorations and sometimes fantastically so, as on the 21-minute title track.

Shortly after the release of Freedom Suite, Felix Cavalier told Billboard magazine, “We don’t believe in violence and we don’t believe in utter passivity. We want to point out a middle road to satisfy both extremes and solve the problems.” Worthy sentiments in our current American era, one that is so divisive that the current president makes Mr. Nixon look like Mr. Rogers (almost). The Rascals legacy of affirmation and compassion, mainly carried on by oldies radio and CD re-issues, got a big boost starting in 2012 with the “Once Upon a Dream” reunion concert and multimedia show that featured all four original members. Produced by “Little Steven” Van Zandt and his wife, Maureen, it brought the group’s good vibes and useful messaging into a 21st century that sorely needs it.