Well, here’s the concluding entry in my survey of recordings in that most star-crossed category, the covers album. Star-crossed in an almost literal way: here are stars performing the songs of other stars.

After listening to so many of these albums I can only conclude that placing one or two well-chosen covers on an album of your own original tunes works a lot better. The reason is a whole collection of tributes usually tends to lack coherence and make even the best artists look like a bar band.

The best way around this is for your covers album to have some sort of concept. The highest-ranking record of Part One of this survey (David Bowie’s Pin-ups) worked so well because of its tight focus. Bowie was paying homage to British bands and key songs from the 1964-67 period, just before he broke thru himself. A similar concept guides the first record reviewed here, the only one other than Pin-ups to gain an A- rating.

Songs From a Haunted Ballroom—The Skids (2021)

While not a household name, most fans of early UK punk will recall this tenacious band who moved down to London from their native Dunfermline in the late 70s. The Skids gained notoriety not just for their tough-guy rep (legend has it that they picked fights in clubs to get their names in the English music press) but also for their aggressive-but-artistic musical approach. That included at least two Brit punk classics: “Into the Valley” and “The Saints are Coming,” both of which are featured here in re-recorded versions.

The rest of Songs From a Haunted Ballroom have an association with the Kinema Ballroom, a vital but volatile music venue in their hometown. The Skids, whose guitarist was future Big Country leader Stuart Adamson, got their start here, playing live sets opening for the likes of the Clash before the place changed over to a discotheque later at night.

Both aspects of the Kinema are celebrated here. Mainstay vocalist Richard Jobson is joined here by ex-Big Country second guitarist Bruce Watson and his guitarist son Jamie Watson. The lads come charging out of the gate with Ultravox’s “Young Savage,” one of many allusions to the club’s stormy history (“Anything goes where no one knows your name”). They tip their hat to the Clash with a nice take on “Complete Control.” In light of the father-son axe duo backing him up, Jobson is obliged to use the song’s proclamation “You’re my guitar hero!” not once but twice.

Elsewhere, there are enthusiastic, high-energy tributes to the Adverts, Sex Pistols, Iggy Pop, Mott the Hoople and Magazine. Just as welcome are some of the less obvious choices like Ace Frehley’s “New York Groove” and Garland Jeffrey’s “35mm Dreams.” The key track is probably their ominous take on David Essex’s glam hit “Rock On.” As an after-hours disco, the Kinema was a magnet for the region’s various violent gangs and apparently “Rock On” was the signal for the trouble to start. Jobson describes the scene in a mid-song monologue as the AV Toi (“the most mental gang in Scotland”) get ready to rumble. Grade: A-

Acid Eaters—The Ramones (1993)

As punk-rock pioneers, the Ramones need no introduction, but once you get past their mid-to-late 70s heyday, they become a lot less examined. By the late Eighties, original bassist and key songwriter Dee Dee Ramone had left, leaving CJ Ramone to man the front line with Joey and Johnny. CJ, who took some lead vocals, was an energizing figure but the band’s run was almost over.

On this, the Ramones’ penultimate studio album, the band matter-of-factly reposition themselves as acid-rock casualties: just look at the disconcerting covert art. Of course, it’s still them so don’t expect Dead-style noodling or Floydish space jams. Opener “Journey to the Center of the Mind” (sung by CJ) may be trippy but it also rocks.

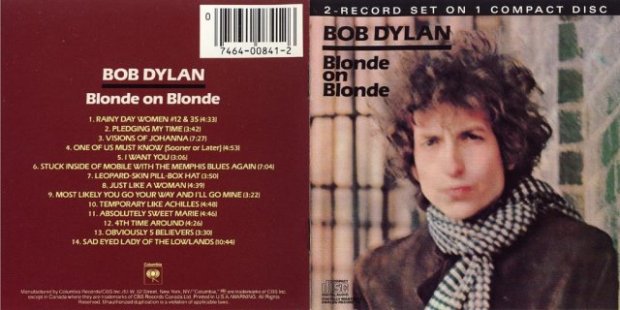

The results here are entertaining if a bit predictable. The Ramones are in a comfort zone when covering their antecedents like the Animals, Seeds and Troggs. And it’s a blast to hear Joey’s long-loved voice singing the Who’s “Substitute” with no less than Pete Townsend guesting on guitar. The same goes when ol’ Bobby Dylan gets the Ramones’ patented faster-and-louder treatment. Their buzzsaw rendition of “My Back Pages” (check out Marky’s triple-time drumming and Joey’s rare lead guitar shredding) gives the Byrds’ celebrated version a run for its money

As usual, though, the results here vary. The Credence vibe (as in “Have You Ever Seen the Rain”) doesn’t seem to suit da brothers and their take on “Somebody to Love” (despite backing vocals by porn star Traci Lords) won’t make any baby boomer forget about Grace Slick. For my money, the Ramones’ best cover came on their next (and last) album Adios Amigos. Their version of “I Don’t Wanna Grow Up,” Tom Waits’ seriocomic take on the old Peter Pan trope, is made all the more affecting by being the final bittersweet salvo of the group’s perpetual teenage rebellion. (The video’s witty animation was done by famed comic artist Daniel “Ghost Story” Clowes). Grade: B (B+ if you add in the Tom Waits tune).

12—Patti Smith (2007)

Rising up from the same Lower East Side scene that birthed the Ramones, New York punk poetess Patti Smith showed a great knack for incorporating others’ work into her own on her revolutionary debut album in 1975. Horses kicked off with her radical recasting of the Van Morrison warhorse “Gloria” with her famous opening line, “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine.” On side two her group seamlessly added “Land of a Thousand Dances” to the outré 9-minute “Land.”

It wouldn’t be until 2007 that the covers-album bug would give Patti a bite. Smith is famously expansive in her fandom, so it’s no surprise that 12 is a grab-bag of songs of different eras and genres. If you want to know how to get from Jimi Hendrix to Tears for Fears to Neil Young in three easy steps, here you are. If you’ve been yearning for a slow-paced version of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” complete with banjo and fiddle, your wait is over.

This will be a pleasurable listen for Patti Smith fans like me. But the fact that her take on “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” is my favorite thing here (despite not being even close to my favorite tune covered) goes to show just how random these records are. Grade: B-

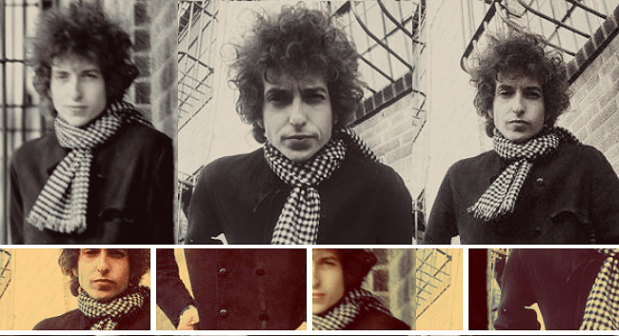

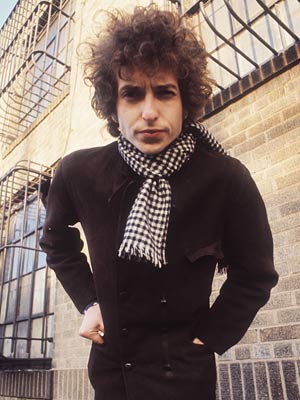

Dylan—Bob Dylan (1973)

This long-derided album can’t be blamed on the artist. A record of traditional songs and covers, they are outtakes from 1970’s lowly-rated 2-LP set Self Portrait It was released against Dylan’s wishes by Columbia Records in “revenge” after Dylan had the audacity to jump ship to Asylum (he came back two albums later).

His largely indifferent takes of various non-originals made up about two-thirds of Self Portrait, and these are the leftovers. There are lackluster tributes to contemporaries (“Big Yellow Taxi” and “Mr. Bojangles”), a few deep oldies (“Spanish is the Loving Tongue” dates to 1907) and a three-hankie Elvis ballad (see below). Bob sings in his appealing “Nashville Skyline” voice but his delivery is lazy, and the record is marred by the overuse of a shrill female chorus too high in the mix. Some have suggested that the ever-cryptic Dylan was engaged in some perverse self-sabotage during this period. I tend to believe it. In his re-issue series, a collection from the same period, called Another Self Portrait, was released in 2013 and it’s freaking great. Grade: C-

Covers—Cat Power (2022)

Chan Marshall, the Atlanta-born singer/songwriter who goes by the stage name Cat Power, has been beguiling fans since she came on the scene in 1992. Her brand of subtle intensity may not be for everyone, but her unique musical stylings make her esp. suitable for doing other people’s material (this is her third, and most recent, covers album). Not everything here sticks the landing, but when it does it’s quietly captivating.

The best to my ears are her artful renditions of two poignant slow numbers. First is the Pogues’ “A Pair of Brown Eyes,” with Marshall accompanying herself on Mellotron (see below). Second is the Replacements’ barroom ballad “Here Comes a Regular.” There are other selections that show the depth of her musical appreciations: Nick Cave’s “I Had a Dream, Joe” and Kitty Wells’ proto-feminist anthem “God Didn’t Make Honky Tonk Angels,” the first C&W #1 hit by a solo woman. On the flip side, she does a song by lesser-chanteuse Lana Del Ray, Bob Seeger’s “Against the Wind” (barely recognizable) and a number from Ryan Gosling’s short-lived group. But with cover albums, variety is the spice of life. Grade: B

Kojak Variety—Elvis Costello (1995)

More “variety.’ First off, I’m glad that this album was named after a store near where it was recorded in Barbados, and not after the charmless TV detective played by Telly Savalas. Secondly, most know that Costello, a generational songwriting talent, has a keen ear for and encyclopedic knowledge of other great tunesmiths—he did a country covers LP (Almost Blue) only a few years into his career. This one also wisely sticks to a plan (the cover touts “Rhythm & Blues, Popular Ballads”) and said tunes are delivered in Elvis’ familiar self-assured style. You get them coming and going: songs by Willie Dixon, Mose Allison, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Little Richard, Jesse Winchester etc. Your favorite will depend on your preference for a particular tune. I love his emotive take on Dylan’s “I Threw It All Away” and esp. his elegiac take on Ray Davies’ bittersweet “Days.” This Kinks Klassic Kover was originally from the soundtrack of the Wim Wenders’ film “Until the End of the World,” where it was also a group sing-along during a campfire scene. Grade: B

Through the Looking Glass—Siouxsie and the Banshees (1987)

The distinctive, imperious voice of goth icon Siouxsie Sioux was well known by the time she and the Banshees decided to do this tribute album of early influences a la David Bowie’s Pin-Ups. And like Bowie, she was able to put a unique stamp on many of the well-chosen covers here. Dark and delectable tunes like John Cale’s “Gun,” the Doors’ “You’re Lost Little Girl,” and Kraftwerk’s “Hall of Mirrors” are naturals for her and delivered in excellent style.

Other tracks go next level: Iggy Pop loved Siouxsie’s version of his nocturnal road-tripping “The Passenger” (which added a neat brass section) so much that he asked to do a later duet version with her. Her goth take on the Billie Holiday nightmare classic “Strange Fruit” is not afraid to sit up right up there in the pantheon. And her eerie vocal on Television’s “Little Johnny Jewel” gives that early punk gem a second life, with guitarist John Valentine Carruthers ably reproducing the song’s infamous 8-note guitar motif while wisely avoiding a go at Tom Verlaine’s nervy, virtuoso solo. Grade B+

I didn’t have time to fully review Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds 1986 covers LP Kicking Against the Pricks but was taken by its closing number. It became a signature song (along with “Georgy Girl”) for fellow Australians the Seekers. Written by Tom Springfield, it seems an appropriate place to close. Like a carnival, cover albums have plenty of fleeting pleasure before they move on to another town, while you turn back to your favorite artists doing original material.