“The American Dream is only a dream, and the American Reality is imperative, a powder-keg situation.” Lester Bangas, 1968.

These are soul-killing times if you are among those who believe that the affairs of the world should be handled with empathy and common decency. The Orange Puke from Hell is back and we’ve gone from the nagging but manageable general anxiety of modern life to the psychic (and sometimes literal) equivalent of having a band of greedy twisted degenerates roaming your neighborhood, out to rob you of your life savings and your medicine, while knocking your grandma to the pavement and kidnapping your neighbor. An administration that has gleefully performed every perdition short of forcing kids to eat lead paint.

While mentally barricaded thusly, I began looking for something to read that would be entertaining but intellectually fortifying. I was seeking something relevant but far removed from the current hellish news cycle and the persistent panic-filled postings of my liberal friends, I came across an unlikely hero in Lester Bangs.

Lester and Debbie Harry on Coney Island back in the day.

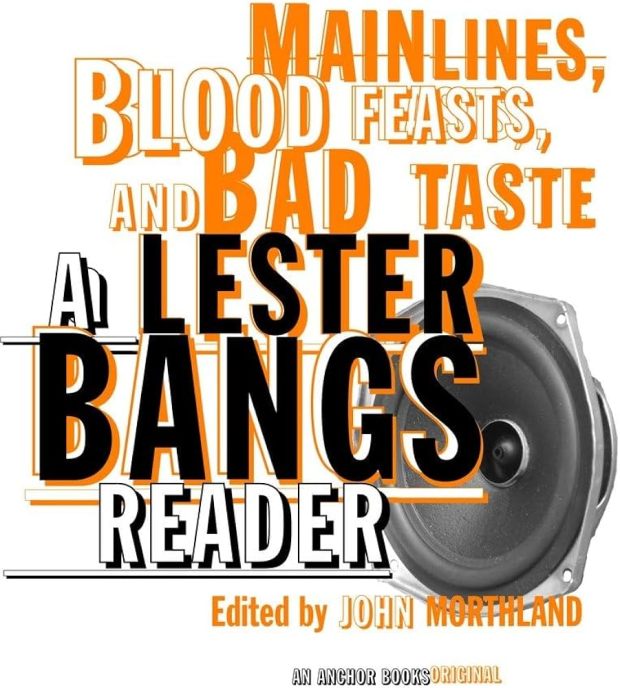

Unlikely in the sense that Bangs, the infamous raconteur and rock critic el supremo, died of an accidental drug overdose in1982. Multitudes of music fans of that era were familiar (if not always in agreement with) Lester’s discursive reviews and articles appearing in Rolling Stone, Creem, the Village Voice and other periodicals. Younger folks might have got to know him from the iconic 1987 collection “Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung,” edited by Greil Marcus or from Philip Seymour Hoffman’s colorful portrayal of him in the 2000 film “Almost Famous.” I had been familiar with Bang’s work since his gleeful hatchet job on Paul McCartney and Wings appeared in a summer of ’76 cover story in Creem. But I was never aware of this second anthology of his work (from 2002) until chancing upon it recently at a used bookstore.

Edited by John Morthland, “Mainlines” is notable for including pieces of a more personal nature, including travelogues and a few entries of a previously unpublished manuscript he wrote at age 19 in that despairing and violent year of 1968—including the astute “Two Assassinations and a Speedy Retreat into Pastoral Nostalgia.” This gives the reader valuable insights (that still ring very true today) into Bangs as the grizzled idealist. But fear not, there’s still plenty of the crazy Lester we knew and loved, with entries like:

“Jim Morrison: Bozo Dionysus a Decade Later”

“Dandelions in Still Air: The Withering Away of the Beatles”

“Stevie Nicks: Lillith or Bimbo?”

“Grace Jones Beats Off”

“Deaf/Mute in a Telephone Booth: A Perfect Day with Lou Reed”

Bring Your Mother to the Gas Chamber!” (his epic essay extolling the virtues of Black Sabbath).

Along the way he also promotes the idea of goody-two-shoes Anne Murray as pop music’s ultimate female sex symbol (“a hypnotically compelling interpretrix with a heavy erotic vibe”) and fully embraces the feminist career move of Helen “I am Woman” Reddy. (“All men but me are spuds. What I would like to see is an all-girl band that would sing lyrics like, ‘I’ll cut your nuts off, you cretins,’ then jump into the audience and beat the shit out of the men there”).

Anne Murray at her sex-symbol peak, with male admirers John, Harry, Alice and Mickey.

You see, Mr. Bangs was in on the great Cosmic Joke. We should be too. Because even at his snarkiest, you could always tell that Lester cared a lot—about music, about culture, about his country. The Cosmic Joke posits that despite all the meaning and purpose we try to attribute to life on earth, we are all headed to the same end (“fellow passengers to the grave” as Dickens put it) so we best embrace our common humanity, give a hoot about something other than ourselves, and have a few laughs along the way.

Bangs had himself plenty of laughs, as you might be able to tell from the titles of the above magazine articles. But the passion and seriousness of much of this collection caught me off guard, in a very good way. “Two Assassinations,” written the day after Robert Kennedy was shot dead, is remarkably astute for a kid still six months shy of his 20th birthday. He declares Kennedy “something of a final straw for me” as he predicts Richard Nixon’s upcoming election and envisions a future America seized by “monstrous social earthquakes.”

Lester on Black Sabbath: “As close as you can get to blood-lust orgies, death, or utter degradation without having to experience them firsthand.”

Of course, music was a saving grace for Lester as it still is for so many of us. Even then, he has a strong propensity for detailing the “aural abyss” of such challenging albums as Nico’s “The Marble Index,” Velvet Underground’s “White Ligh/White Heat” and Pil’s “Second Edition,” among other personal favorites. In an age of hit-and-run social media opinions, it’s a throwback reading pleasure to see Bangs spend pages wrestling with the patchy quality of hero Miles Davis’ early 70s output or painstakingly lambasting Bob Dylan for the “Mafia Chic” misjudgment of his ill-advised paen to psychotic mobster Joey Gallo.

Many contemporary readers will be justifiably put-off by Bangs’ casual use of insensitive epithets (spade, homo, bitch) but maybe what we’ve gained in sensitivity we’ve lost in critical thinking. In his prime years, in the age of Nixon and Vietnam, he saw the cruelty of the right but also the rigidity of the New Left and took on life with endless creative drive and steely purpose, warning us way back then about the vast social chasms awaiting America and the urgent individualism needed to keep your head above the waters that would otherwise have you drowned.