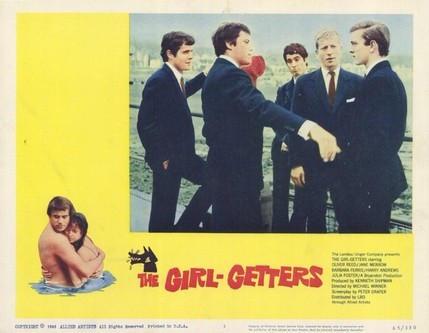

The Girl-Getters (a.k.a. “The System”)

Directed by Michael Winner—1964—93 minutes

Starring Oliver Reed, David Hemmings, Jane Merrow, Barbara Ferris, Julia Foster & Harry Andrews

The under-recognized Michael Winner film “The System” represents a great lost missing link in the evolution of British cinema. Re-named “The Girl-Getters” for the American market and released just three months after “A Hard Day’s Night,” it rings out with the ascendant spirit of the youth films just coming into vogue. But it still owed a debt to the so-called “kitchen sink” dramas of the late 50s and early 60s, those gritty films like “A Taste of Honey,” “This Sporting Life” and “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning” that featured characters hemmed in by class boundaries, societal expectations and (more often than not) unexpected pregnancies. A 26 year-old Oliver Reed stars as Tinker, a wily beach photographer and ladies’ man in a seaside holiday town on England’s south coast. He heads up a gaggle of young men who have developed “The System” to maximize their success rate in the time-honored British endeavor known as “pulling the birds.”

The gang take inventory of the “finches.”

Right out of the gate, “The Girl-Getters” is a movie to savor. The shimmering B&W cinematography is by a talented up-and-comer named Nicolas Roeg. To the nifty uptempo strains of the Searcher’s theme song, we watch the guys speeding around in their roofless, backfiring jalopy. They drive to a neighboring train station to drop off a couple of their number so the incoming young ladies can be chatted up on the train before it even arrives in town. (“Get into the System” the Searchers sing, or at the end of the line “you’re alone”). Over the last two weeks of August, the gang and a rotating cast of the fairer sex will play out the summertime rituals on the bright-white promenade, in the shadows under the pleasure pier and inside the dancehalls and snack bars—as well up in Tinker’s attic loft. Although it’s not hard to guess that narrative complications will scratch up the film’s carefree surface, “The Girl-Getters” never gets as low as the often-embittered kitchen sinkers. Realistic rites of passage have replaced tragic pitfalls on the road to adulthood.

A lot of credit to the film’s success goes to Mr. Reed’s finely-tuned performance as the rakish but astute (even philosophical) Tinker. With none of the coarse mannerisms that sometimes dragged down future roles, Reed’s broad, handsome face and piercing bright eyes are at the center of most every scene. He meets his match in level-headed society girl Nicola (Jane Merrow), a stunning brunette fashion model who’s in town to check in with her aristocratic father and have some fun between assignments. Many movies would exxagerate the unlikely pairing: Nicola is all that: she’s got the looks, personality, money and use of her dad’s Buick Riviera. Tinker may be boss of the boardwalk but it’s a short season and the specter of a long, lean winter hangs over the locals whose credo is (according to him) “take what you can from the visitors, gather nuts against the hard winter.” But Winner’s naturalistic direction and Peter Draper’s clear-eyed script won’t allow for easy clichés. The pair’s bubble-blowing interlude and demure way of asking each other’s age hint at their relative innocence even as adult experiences beckon. They see in each other a possible way forward: for Tinker, Nicola may be a catalyst to get out of his provincial rut and better himself professionally in London; in Tinker, Nicola sees a native intelligence perhaps preferable to the entitled snobbery of her male friends back at the palm court.

It was not all marketing hot air when posters for “The Girl-Getters” proclaimed it was “an adult film for teenagers and a teenage film for adults.” Maybe that’s because the cast, brimming with the youthful energy typified by the rise of the Beatles, fell neatly in between those two broad demographics. A fresh-faced David Hemmings, as the newest addition to the boy’s club, is introduced to the ways of the “grockles” (tourists) and the inner workings of The System, but by end is planning on ways of improving it. Barbara Ferris does a sympathetic turn as the local would-be girlfriend of Tinker and the wonderful Julia Foster makes a brief but winning appearance as a party girl all too ready to offer Tinker the dreaded domestic arrangement offer after a brief fling. (I was a little young for this film during its brief American theatrical run, but developed a mad crush on Julia three years later in 1967 when she was the female lead in the Tommy Steele musical “Half a Sixpence.”) Veteran British hard-guy actor Harry Andrews steps up as the “Establishment” figure, playing Tinker’s boss, the no-nonsense proprietor of the Sunny Snaps photo lab.

A grockle’s eye view of Tinker

Michael Winner certainly deserves credit for organizing this excellent cast and script into a time-tested end product that totally avoids the silliness that infected slightly later swinging British Beat Cinema entries like “The Knack” and “Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush.” But Winner (who died in 2013) was more of a journeyman director probably most remembered for the indefensible “Death Wish” series he would do with Charles Bronson. The real production star is Nicolas Roeg. His photography during Tinker and Nicola’s romantic idyll on a remote cliff-backed beach is one of my favorite things ever by him, comparable to Ingmar Bergman’s 1953 young-love classic “Summer with Monika.” It is on this same scenic beachfront (with its abandoned hamlet) where the film ends. One of Tinker’s men has gotten himself married (as usual in these films, a pregnancy is involved) and the young locals combine an end-of-the-season bonfire with a strange, primal ritual involving bridge-and-groom effigies and scarifying masks. Instead, of the hopeless undertow that pulls down supposedly “carefree” movies like “Georgy Girl,” this group looks like they are smoking out the demons and putting trust in their collective friendship. The morning after, as Tinker gives Nicola a “bye-for-now” wave and joins his pals (both male and female) for one last frolic on the sand, you are given hope in a sensible implied outcome. These young people may have shaken off the shackles of confining post-war British mores, but neither do they look like they are going to be bamboozled by the illusions of a totally-liberated Sixties mindset. You expect that they’ll be working a sensible middle path to a place where things will end up just fine.

My next book, “Rock Docs: A Fifty-Year Cinematic Journey” (1964-2014) will be released later this year.

This post is my contribution to the Classic Movie History Project Blogathon, hosted by Fritzi at Movies Silently, Aurora at Once Upon a Screen, and Ruth at Silver Screenings. See the link below to see a list of the other 90 amazing entries spanning the eras from the beginning of cinema up to 1975…