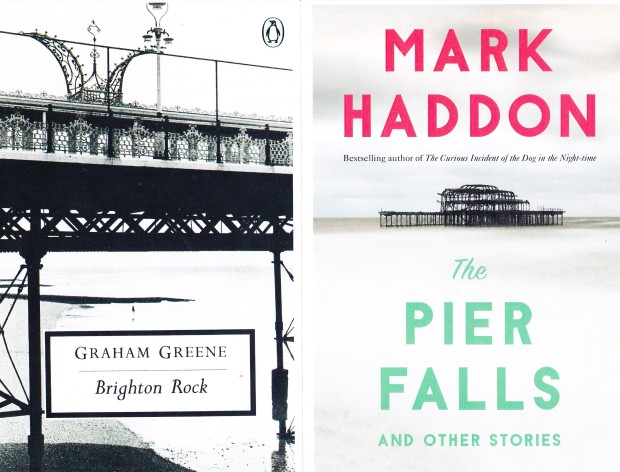

Text and above photo by Rick Ouellette

It was one of the most celebrated of the 85 pleasure piers built during England’s Victorian era. In 1870, a visiting Napoleon III called it “Britain’s finest structure.” It’s grand 1600-foot oriental profile could be regarded as the people’s answer to the nearby John Nash-designed Royal Pavilion, the exotic getaway built for the Prince Regent (the future King George IV) that had been completed about four decades earlier. In its 109 years of operation (1866-1975), Brighton, England’s West Pier was a topmost playground for everyday folk on their seaside holidays. It was one described as a “luxury liner that never left its mooring” and where the anyone could have first-class accommodations for a small entrance fee. Today, however, only a small portion of the pier’s steel superstructure rises above the chilly Channel waters off the beach. West Pier’s story is one of extremes in pleasure and and calamity.

During its century-plus in operation, the pier variously featured a huge games pavilion and a concert venue with a house orchestra, amusement park rides, slot machines, ballrooms and tea rooms, pubs, and eateries. It was also known for the sale of candy floss (cotton candy) and its signature “Brighton Rock” crystal confection. Author Graham Greene used the locale and the Brighton Rock name for the title of his totemic 1938 novel of crime and Catholicism. West Pier also serves as a backdrop for the Who’s stormy 1973 rock opera “Quadrophenia.” (The band’s earlier hit “Pinball Wizard” is sung from the point of view of a lad who loses to Tommy despite knowing every machine “from Soho down to Brighton”).

But in the end, West Pier was just as unlucky as it was celebrated. While the Brighton Pavilion and its sister promenade Palace Pier, remain popular local landmarks, the West Pier couldn’t sustain it’s boast of being “the best pier.” Much of its central decking was removed in 1944 to prevent enemy landings. Its popularity declined in the post-war era, and more downscale amusements superseded the grand concert hall and the fashionable boardwalk deck. Structural decay commenced with dis-investment and the pierhead was closed in 1970. Maintenance costs for such an ambitious structure scared away potential new owners and the whole place was off limits five years later.

West Pier became a sort of plebeian version of the old romantic ruined castle. The 1982 book “Dead Tech: A Guide to the Archaeology of Tomorrow,” by photographer Manfred Hamm and writer Rolf Steinberg was in the vanguard of an aesthetic that would spur the urban exploration phenomenon. It featured several sad but alluring photos of West Pier, placing it in the same obsolescent class as a graveyard for old steam-powered trains and the abandoned launching pads of the Apollo space program. It attracted trespassers and vandals and by 1994, when I visited Brighton the foot of the pier had been cut off from the land in an attempt (ultimately unsuccessful) to stop further damage.

This beached leviathan was destined for a series of indignities that would all but wipe it off the map while other English piers from Blackpool down to Southend-on-Sea would continue to thrive. The cyclonic Great Storm of 1987 caused a partial collapse. Another severe weather event in 2002 caused the concert hall to cave in. Two major fires delivered the knockout punch in 2003. Both were considered of suspicious origin; I would love to hear any story of how arsonists accomplished this wicked feat, considering the pier was cut off from land and only accessible from structurally unsound steel supports.

Even in the skeletal shell form it was reduced to, West Pier continues to fascinate. It’s been used for a giant laser light show and the 2003 fires are re-lived in singer Nick Cave’s novel “The Death of Bunny Munro.” Most notably for me, the fictional 1970 collapse of West Pier is the basis of writer Mark Haddon’s astonishing lead story in his 2016 collection “The Pier Falls.” In remarkably precise, present-tense detail, Haddon creates an immense, harrowing and heartbreaking disaster out of thin air, after four introductory paragraphs of a normal day out in Brighton. But why? Hasn’t it suffered enough? There must be an aura hanging over West Pier’s skeleton that makes it a subconscious marker of the mortality that awaits even the most powerful of persons or things. It’s that ineffable quality that makes our modern ruins so irresistible to ponder.