The road to ruins is paved with both the best and worst of intentions. Since time immemorial, people have either through either direct experience or artistic representation, sought communion with the relics of the man-made glories of the past. The picturesque ruins of the Roman Empire have been tourist sites of one sort or another since forever. These early antiquities give an example of the duality of their appeal. The lofty remains of temples and the Roman Forum stand for the idealism of spirituality, civic and social activity, enterprise and an advancing civilization. The nearby Colosseum, one of the world’s most recognizable ruins, is a wonder of ancient design and its building principles has been a model of stadium design ever since. But the more base appeal is the notion of all the gladiatorial battles and mass killings that went on there, often under the guise of a grim sporting event, as depicted in Hollywood spectacles on more than one occasion.

Classic ruins. The Roman Forum and Colosseum, photos by Ryan Ouellette.

With the advent of widespread air travel in the middle of the last century, international touring grew exponentially. Combine that with the fact that the earth’s population has more than doubled in that time and it’s not hard to understand a problem that anyone who’s been anywhere famous lately has encountered: the world is being overrun by tourists. That doesn’t necessarily mean that one should skip the capitals of Europe, the Great Wall of China, the ghostly remains of Pompeii or the top of the Empire State Building—just be prepared to have lots of company. Given the dense points-of-interest overcrowding, coupled with the speed in which modern technological “progress” makes obsolete that which was recently cutting edge, it’s probably not much of a surprise that many people have gone off the beaten path to take history into their own hands.

In the last couple of decades, a whole sub-culture has sprung up under the umbrella phrase “urban exploring.” In general, this brings to mind trespassing photographers and spelunkers of the boarded-up building variety. Favorite objectives included shuttered asylums, closed factories and bankrupted theme parks. The thrill of the illicit is a major factor here even if most of these photographers are sensitive to the backstory of such locations. Still, there was a time (and one not entirely in the past) where the websites of these urban explorers attracted groupie-like followers who littered the comments section with gushing praise over just how “creepy” it all is.

The U.S. is dotted with the remains of hundreds of closed state hospitals or, in the case of the shuttered Fernald School in Massachusetts, fearsome institutions where children with developmental issues real or greatly exaggerated, were once warehoused and even experimented on. Photo by Rick Ouellette

As the dogged pace of technological obsolescence has continued apace, a newer sensibility has taken place: one that strives to understand the complex social and economic reasons why such relatively new man-made achievements fall into disuse and abandonment so quickly, sometimes within a couple of generations. While the voyeuristic tendencies remain—the regrettable phrase “ruins porn” has gained traction—this soul-searching aspect is often a driving force behind the books, articles and websites on this subject.

Rubble tourism is now having its day. Instead of risking arrest, avocational photographers like myself can sign up to tour these once forbidden locations. Sometimes, the nominal purpose can be to inspire a call for landmark designation or renovation instead of demolition. I have taken workshops with two accomplished photographers who run them, sometimes together, and their books (“After the Final Curtain” by Matt Lambros and “Abandoned America” by Matthew Christopher) are reviewed below along with info about their tours. But first to begin at the beginning:

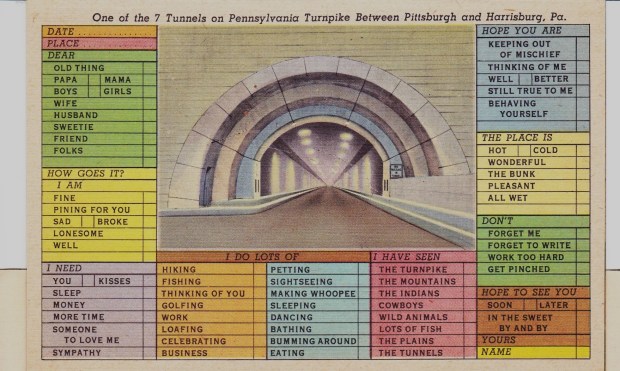

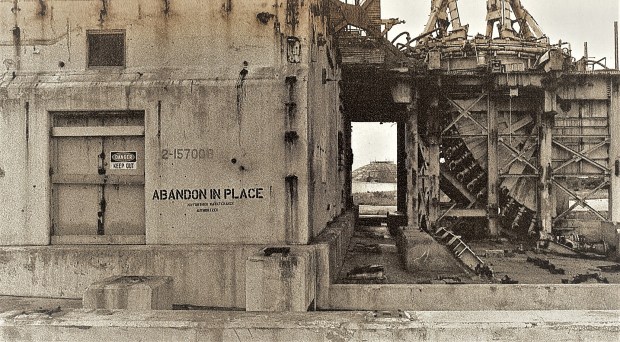

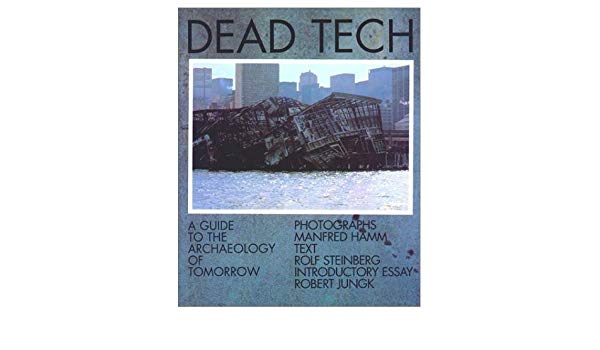

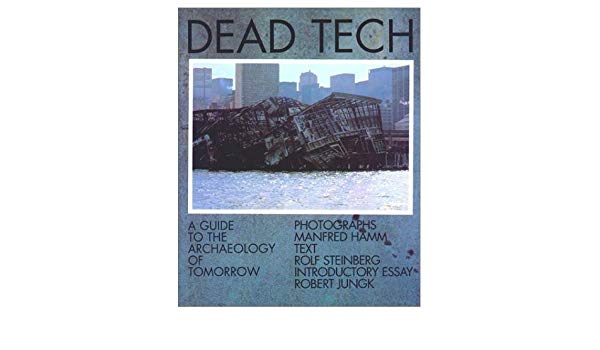

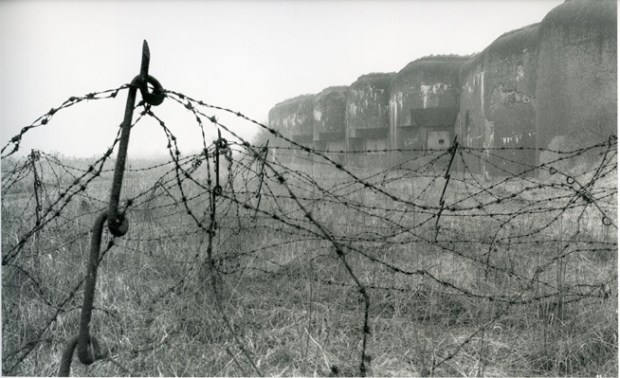

Although I’ve always been pre-disposed to notice the vestiges of a not-distant past (a trait that I have seemed to passed on to my son) this sensation never really had a name or focus for me until I saw (and bought) a copy of “Dead Tech: A Guide to the Archaeology of Tomorrow.” This book was first published in Germany in 1981 and an English version came out a year later, interestingly under the auspices of Sierra Club Books. With its enigmatic cover photo of a New York ocean liner terminal crumbling into itself on the Hudson River waterfront, “Dead Tech” had an immediate impact on me. Across nine themed chapters of evocative photographs by Manfred Hamm and historically insightful text by Rolf Steinberg, we are treated to a captivating catalogue of the recently defunct remains of world-war battlements, ships and airplanes, auto graveyards, abandoned space launch platforms, closed power plants and pleasure piers and quickly obsolete transportation systems.

The photo at the top of this post is from “Dead Tech” and shows the vestiges of the Gemini rocket launch pad in Cape Canaverel

Photo by Rick Ouellette. Not long after obtaining a copy of “Dead Tech” I took to photographing similar (or the same) locations when I had the chance. One of them was Manhattan’s West Side Elevated Highway. It was one of the world’s first freeways, started in 1929. It’s well-intentioned aim was moving vehicular traffic off the surface of 11th Ave., then nicknamed “Death Avenue” because of the dangerous intermingling of autos and freight trains over 106 (!!) grade crossings. Despite the proud winged-wheel symbol seen here—–the insignia of Mercury, patron of commerce and travel—the highway was all but obsolete by the time it was completed in 1951. Interstate trucking had replaced most of the freight trains anyway and when an overloaded truck caused a section to collapse in 1973, the West Side Highway was all but done. By 1989 had been completely dismantled.

“Dead Tech’s” provocative introduction is by Austrian author Robert Jungk, described on the inner flap as an “uncomfortable futurist.” Is he ever. Jungk understood the collective existential dread of a post-war society living under the nuclear shadow, one of his main subjects. Jungk, whose surname invokes both the words “Jung” and “junk,” is no romantic when he contemplates these sites. They speak to him from a deep psychic well of historical human suffering. He writes, “Time does not only heal all wounds, it also blots out the memory of pain.” He sees the detritus of the modern world as not only wasteful but terminally short-sighted and accuses mankind of not admitting past mistakes before diving headlong into his next misadventure. This point is well taken even as you get the feeling that Robert wouldn’t be the most fun person to talk with at a party—about these ruins he says: “They are not uplifting but ludicrous and horrifying at the same time.” But their ghostly attraction is undeniable and hopefully a red flag to be heeded. (The grim stack of crushed cars piled up like a pyramid at a Philadelphia scrapyard is no one’s idea of a tourist trap). It wasn’t all gloom-and-doom with Jungk. He advocated for a new “gentle technology” and ran for president of Austria on the Green Party ticket before dying in 1994.

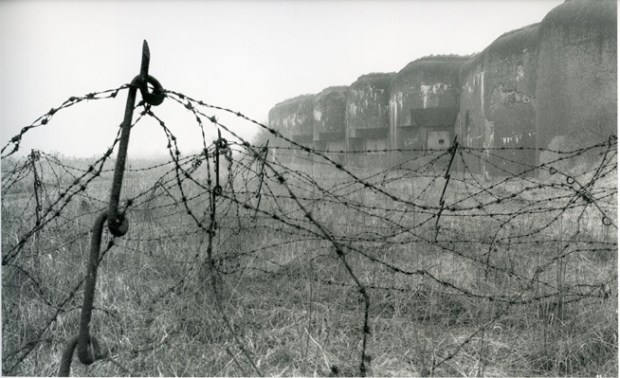

A remaining section of the Maginot Line in France. Photo by Manfred Hamm from “Dead Tech.”

********************************************************************************

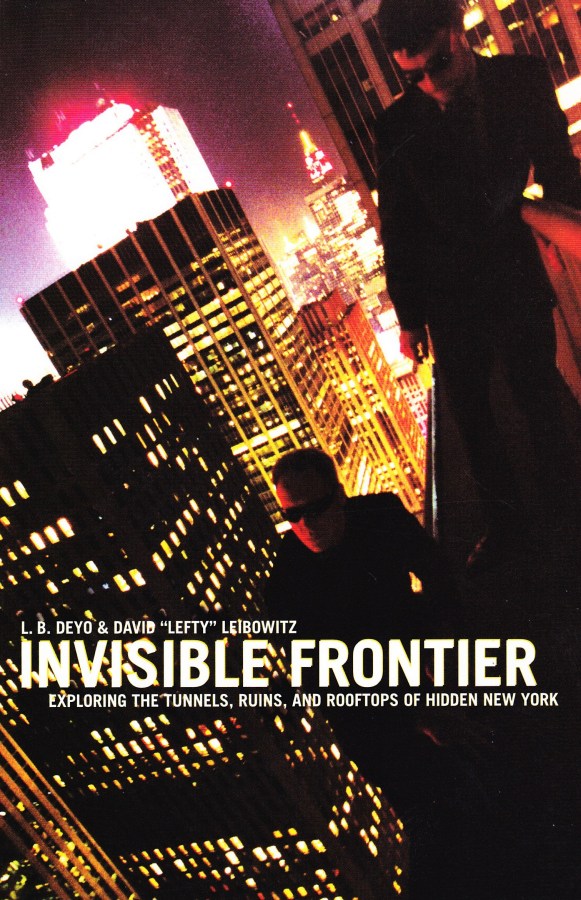

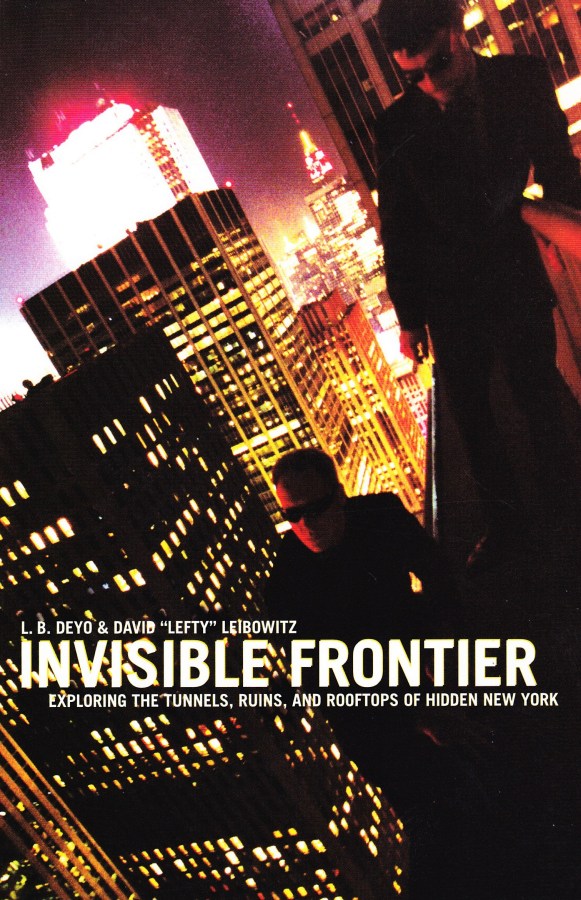

Still, the fascination continued. In the summer of 2001, a group of daring (and incongruously well-dressed) young adults set off on a series of audacious expeditions infiltrating the core of New York City’s daunting superstructure. They were led by two guys calling themselves L.B. Deyo and David “Lefty” Leibowitz, who also documented these exploits in a fascinating paperback called “Invisible Frontier.” In the admirably zany opening chapter, they attempt to traverse the Old Croton Aqueduct tunnel from an entry point in the Bronx’s Van Cortlandt Park to the Central Park area, where it used to pour its water into a giant reservoir that supplied the growing city in the second half o fthe 1800s. This would have meant crossing into Manhattan via the vertiginous High Bridge over the Harlem River. Deep collection pools, not to mention the suffocating dankness and the bats, have them eventually turning back: but not before we are treated to our first taste of the book’s curious mix of historical background and snarky banter. The “Jinx” team members dress in dark business suits—and evening dresses for the ladies—and tend to plan their missions using semi-satirical commando jargon.

Over the course of that summer the group plumbed further depths (the long-closed 1904 City Hall subway station) and then clamber up to the rooftops of Grand Central and the Tweed Courthouse, all done with cheeky aplomb (“Today we will discover a pinnacle of New York’s architectural past hidden from the prying eyes of the slovenly modern citizen”). “Invisible Frontier” culminates in a mad-dog ascent to the top of one of the George Washington Bridge towers and a six hundred feet-in-the-air epiphany. But the authors also quietly note that this off-limits triumph came a mere three days before the events of 9/11, after which a brave new world of heightened security and heightened suspicions would come into play. The Jinx group ceased their trespassing ways but its point had already been made. That despite all the building and development and now extra surveillance, “all around us lay the ruins of a golden age of style,” a half-hidden world that will live on.

********************************************************************************

A bombed-out German bunker in Normandy. Photo by Rick Ouellette

World War Two sites, especially in Normandy, are of course enormously popular tourist destinations and have been for decades. But popular also means crowded, esp. during the summer. For the discerning war ruin devotees, the PBS series “Nazi Mega Weapons” (and by extension “WW2 Mega Weapons”) will give viewers a good look at, and the place names of, many crumbling mementoes of Adolph Hitler’s megalomania. These range from the launch pads of V-2 rockets to supposedly impregnable super-bunkers, in locations stretching from the Channel Islands to the old Eastern Front. Curiosity peaked, it’s easy in this Internet age to find even the most obscure of these sites, or to find organizations or individuals who give tours of such World War or Cold War points of interest.

********************************************************************************

In the middle and late Eighties, American photographer Brian Rose undertook the extensive (and sometimes risky) task of documenting the vast system of walls, fences, no-man lands and guard posts that ran like a geopolitical scar separating the democratic West from the Soviet-dominated countries of Eastern Europe. The project that would result in the book “The Lost Border: The Landscape of the Iron Curtain” began when the “zero-sum logic” of this rigid ideological system—and the architecture which enforced it— was still very much in play. Just as remarkable about this artificial frontier that divided countries, towns and even streets, was the speed at which this system collapsed, as one communist state after another abdicated control after the events of late 1989.

The Iron Curtain stretched from the Black Sea to the Baltic, but Rose began his project in it’s most famous and heavily fortified section. The Berlin Wall was erected in the early 1960s to keep people from the eastern sector from escaping into the encircled enclave to the west. (Although the East German government insisted at the time that it was built to keep “fascist adventurers” from getting in). Rose’s photos deftly display both the physical and physic disconnect between two distinctly different societies sitting cheek-by-jowl. We see tourists in brightly-colored clothing peering into a grim East Berlin from a viewing stand and streets and transit lines cut off at the knee. Farther away from the cities, the border can get pretty diffuse: the fences get smaller and the borderline can be nothing but a small warning sign; one photo shows and easily stepped-over chain dividing a beach. Rose learned early on from the locals not to risk it. A few years after starting the project all this fearful apparatus became obsolete, making “The Lost Border” a valuable socio-political record over and above the high quality of his images.

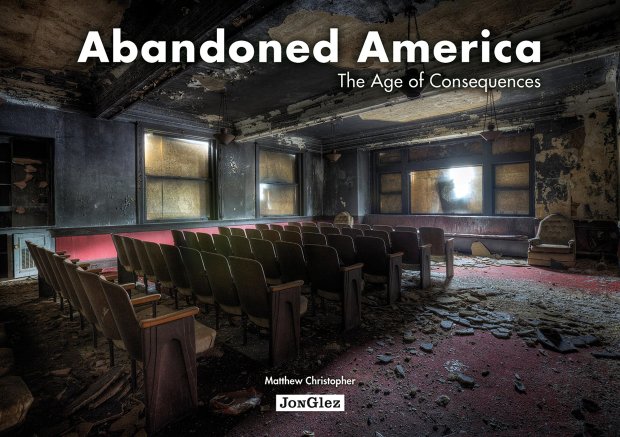

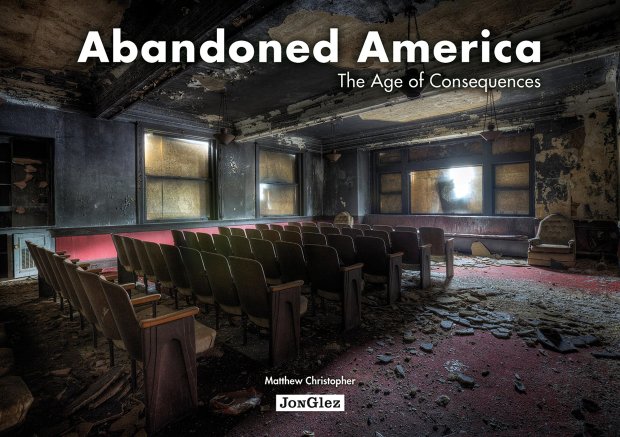

It was at the end of World War II and for the next couple of decades after that the U.S. industrial and economic might was at its peak. Of course, a lot has changed this then and never more viscerally than in photographer Matthew Christopher’s book “Abandoned America: Age of Consequences.” Page after page feature the devastated remains, in beautifully rendered hi-def photos, of buildings magnificent in scope and/or noble of purpose. These eye-popping images of derelict power plants, factories, trade schools, churches, fraternal lodges and communal vacation resorts speak powerfully of a severely shredded social and economic fabric. (Most of these locations are in Midwest and Mid-Atlantic states). These ruins say a lot of what we don’t want to hear.

Photo by Matthew Christopher

Back from the late 19th century through to the middle of the 20th, when most of these places were constructed, there were political and social differences aplenty, often profoundly so. But there was also was a common-denominator civic pride as a baseline, not to mention a colossal industrial sector that not long ago was the envy of the world. This formed the basis for the eventual building up of a solid American middle-class and a wavering but respectable network of aid and comfort for those in legitimate need.

Not only do those “permanent achievements” look a lot less invariable by the day and it’s not just callous, cost-cutting corporations to blame. The national political dialogue (such as it is) about what to do has become the worst sort of zero-sum game. The idea that the two sides of the aisle would have a clash of ideas and each would come away with some of what they wanted is almost laughably quaint now. But there is nothing funny in the evidence of this decline seen in Christopher’s haunting images.

******************************************************************************************

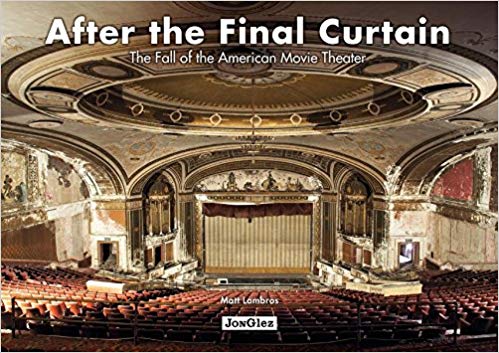

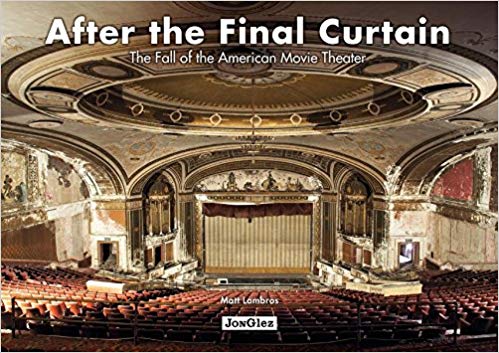

Matt Lambros had photographed close to 100 closed theaters and chose twenty of the most prominent for his sumptuous coffee table book “After the Final Curtain.” His fascination with these opulent movie palaces began with personally discovering several near where he lived in New York City. Some still open, some boarded up. Soon he was travelling the country and realizing that almost any city in America with some critical mass of population, had at least one of these places, in widely varying conditions but often the worse for wear. These places were built in the first few decades of the 20th century, when people rather expected their entertainment was to be provided in lush, classically-detailed venues and developers provided for such.

But the short and often discouraging history of these theaters can be representatively seen in the case of the stupendous Loew’s Poli Theater in Bridgeport, Connecticut (a sweeping view of which graces the book’s cover). In opened in 1922, after a two-decade period which saw the city’s population double from 70,000 to more than 140,000. Still, not a megalopolis but enough that the growing port city could support a second auditorium next door and connect it all with a hotel and shops. Over 3000 people could watch vaudeville and silent films in the main hall and it made a successful switch to the talkies. But y’all know what happens next: TV, surburbanization, the income inequality that afflicted many older downtowns. The 50-year timeline of the Loew’s Poli is not uncommon: it soldiered on into the mid-century, underwent name changes and new usages and, like many others, ended as an adult-film house before closing in the 1970s. Some of these places have been re-furbished but it’s always an extremely costly proposition and many still languish.

If you’re interested in visiting these type of places (and esp. interested in photographing them) your’re in luck. Both Matthew Christopher and Matt Lambros run workshops where you can click your cameras at places like this (sometimes the “Two Matts” run these events together). See below for their websites and more info. And wherever you go, may all your travels be “ruined.”

https://afterthefinalcurtain.net/

https://www.abandonedamerica.us/

Photo by Rick Ouellette. The old Paramount Theater in Springfield, Mass. (later the Hippodrome nightclub). From a photo workshop I did with Matt lambros and Matthew Christopher.