Visitors—Directed by Godfrey Reggio—2013—87 minutes

Godfrey Reggio’s “Visitors” is probably the best black-and-white photo gallery exhibit ever made into a motion picture. I’m kidding, but only to prep you about what to expect with Reggio’s slow-lane meditation on what it may feel like, deep down, to inhabit our fast-lane 21st century. “Visitors” is a patient, visually sumptuous and occasionally frustrating film. It is also one that, in its wordless succession of images and music, calmly cajoles us to take stock of ourselves.

Reggio is still best known for 1982’s “Koyaanisqatsi,” his sensation-causing experiment in depicting a “life out of balance.” It started off slowly with contemplative images of the natural and indigenous worlds before eventually building up to frantic climax with sped-up images of big-city commuters and commotion, all matched to the ever-increasing tempos of Philip Glass’ celebrated soundtrack.

Two other films followed in the same vein: “Powaqqatsi” from 1988, and 2002’s “Naqoyqatsi.” The director has said that, like those earlier films, “Visitors” was about “humanity’s trancelike relationship with technology.” That may be true in a sense, but this 2013 work has a far different feel than the “Qatsi Trilogy.” Those works tended to bludgeon the viewer with relentless images of a world being nearly crushed under the weight of its own industrialization and materialism. It’s a point well taken, but also one which got tiresome over the course of three films. After a while the accelerated rats-in-a-maze images of train commuters going up escalators felt elitist. When you get right down to it, these are just productive citizens on their way to work.

Here, we are asked to look straight into the faces of our fellow humans, of all races and ages, not to mention meeting the haunting gaze of a female Lowland gorilla, a signature image of this film. Often, these shots last 90 seconds or more. These cinematic staring contests made for a somewhat squirmy viewing experience when I saw “Visitors” in a theater on its original release. In the solitary comfort of one’s home, this same device feels like a bridge to feelings of deeper human connections. If that sounds counterintuitive, so be it. It is so gratifying to take an empathetic look at our fellow travelers free of both the grievance politics and the ankle-deep identity affirmation that draw us away for our collective interests.

Some of this cinematic strategy must relate back to the director’s life story. Reggio was born in New Orleans in 1940, but by age 14 he had left home and soon became a Christian Brothers monk, spending his time in silence, prayer and mediation until age 28 (giving fair indication of his non-verbal filmmaking philosophy). He long since relocated to Santa Fe where he worked with troubled youth and was turned onto cinema after seeing the related “Los Olvidados” by Luis Bunuel. The devastations of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 led Reggio back to his stricken hometown and his location photography, as impressive as ever, features many locations in and around the Crescent City.

There are elegiac, time-lapse images of New Orleans’ Six Flags amusement park and Mercy Hospital (both closed post-Katrina), vaulted cemeteries and ghost-like bayous. These are beautifully filmed in a process that resembles B&W infrared still photography: think black skies and glowing white foliage.

Near the end, we return to an opening shot of sailing serenely over the surface of the Moon, like alien visitors gazing at the marbled planet Earth, accompanied by Philip Glass’ tranquil score. We have spent the last 80 minutes in a queer sort of communion with ourselves and our environment, not always sure if we are the watchers or the watched but assured that in the end it’s all the same. In the age of dizzying discord and snap judgments, Reggio’s hypnotic and humane film invites us to stare at the world until we see ourselves in it, along with everyone else.

But director Shah makes no mistake in pointing out that the National Front had made race prejudice an “acceptable point of view” in Britain at that time. This extended to some prominent old-guard rock stars. Included in this shameful category was David Bowie (who opined that the nation could “benefit from a fascist leader”) and Rod Stewart, who suggested (from the comfort of his new home in Los Angeles) that all of the UK’s immigrants “should be sent home.” Most egregious was Eric Clapton who, during an infamous 1976 concert in Birmingham, launched into a drunken racist tirade (“get the coons out”) while also asking minority fans in the audience to raise their hands and chanting the NF slogan “Keep Britain White.”

Of course, Saunders was all over this, bitterly criticizing Clapton (who built his career on the blues) of musical colonialism and suggesting that the guitar-god may be suffering from a touch of “brain damage.” True, punk did sometimes dabble in Nazi iconography, but you always got the feeling this was for shock value and not the sort of contemptible white privilege on display in the examples above.

An enjoyable aspect of White Riot is the emphasis on the inner workings of Temporary Hoardings and the current interviews with staffers like “Irate” Kate Webb, Syd Shelton and Lucy Whitman. The grassroots organizing, in an age before cell phones and the Internet, is inspiring as are the animated re-creations pf the newspaper’s cut-and-paste punk aesthetic.

But director Shah makes no mistake in pointing out that the National Front had made race prejudice an “acceptable point of view” in Britain at that time. This extended to some prominent old-guard rock stars. Included in this shameful category was David Bowie (who opined that the nation could “benefit from a fascist leader”) and Rod Stewart, who suggested (from the comfort of his new home in Los Angeles) that all of the UK’s immigrants “should be sent home.” Most egregious was Eric Clapton who, during an infamous 1976 concert in Birmingham, launched into a drunken racist tirade (“get the coons out”) while also asking minority fans in the audience to raise their hands and chanting the NF slogan “Keep Britain White.”

Of course, Saunders was all over this, bitterly criticizing Clapton (who built his career on the blues) of musical colonialism and suggesting that the guitar-god may be suffering from a touch of “brain damage.” True, punk did sometimes dabble in Nazi iconography, but you always got the feeling this was for shock value and not the sort of contemptible white privilege on display in the examples above.

An enjoyable aspect of White Riot is the emphasis on the inner workings of Temporary Hoardings and the current interviews with staffers like “Irate” Kate Webb, Syd Shelton and Lucy Whitman. The grassroots organizing, in an age before cell phones and the Internet, is inspiring as are the animated re-creations pf the newspaper’s cut-and-paste punk aesthetic.

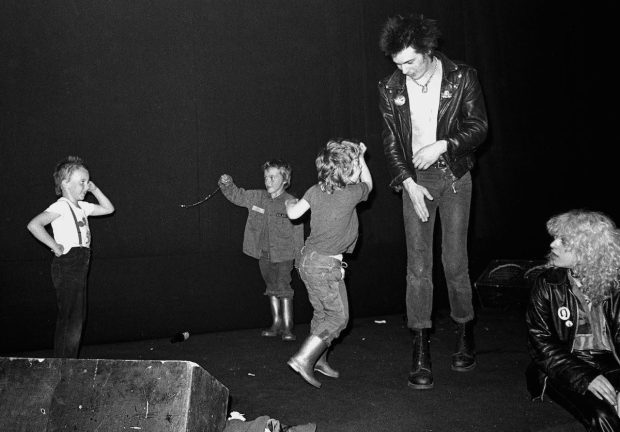

After months of rumbling with NF marchers and right-wing yobs, RAR had its moment in a bravura march from Trafalgar Square (see photo above) to Victoria Park, the ensuing demonstration and concert (headlined by the Clash) drawing close to 100,000 folks. The National Front fizzled at the polls in the ensuing general election (1.3%) but the vote also saw the election of Prime Minister Maggie Thatcher, who employed the dog whistle instead of the boot to exploit the cause of white grievance. Yet the celebration of cultural diversity promoted by Rock Against Racism has taken hold over the decades, even as populations seem intent on going backwards. So the struggle goes on, but Rubik Shah’s compelling work can act as a valued piece to show us again the way forward.

**************************************************

You can check out the excerpt of my book “Rock Docs: A fifty-Year Cinematic Jorney” at

After months of rumbling with NF marchers and right-wing yobs, RAR had its moment in a bravura march from Trafalgar Square (see photo above) to Victoria Park, the ensuing demonstration and concert (headlined by the Clash) drawing close to 100,000 folks. The National Front fizzled at the polls in the ensuing general election (1.3%) but the vote also saw the election of Prime Minister Maggie Thatcher, who employed the dog whistle instead of the boot to exploit the cause of white grievance. Yet the celebration of cultural diversity promoted by Rock Against Racism has taken hold over the decades, even as populations seem intent on going backwards. So the struggle goes on, but Rubik Shah’s compelling work can act as a valued piece to show us again the way forward.

**************************************************

You can check out the excerpt of my book “Rock Docs: A fifty-Year Cinematic Jorney” at